Martha Tabram

The night before her murder, Tabram was drinking with another prostitute, Mary Ann Connelly, known as “Pearly Poll”, and two soldiers in a public house, the Angel and Crown, close to George Yard Buildings. The four of them paired off, left the public house and separated at about 11:45 p.m., each woman with her own client. Martha and her client went to George Yard, a narrow north-south alley connecting Wentworth Street and Whitechapel High Street, entered from Whitechapel High Street by a covered archway next to The White Hart Inn. George Yard Buildings were on the eastern side of the alley, near the northern end to the back of Toynbee Hall. The Buildings were a former weaving factory that had been converted into tenements. Today, the location is called Gunthorpe Street and residential flats stand on the site of George Yard Buildings. Pearly Poll and her client went to the parallel Angel Alley.

In the early hours of the night, a resident of the Buildings, one Mrs. Hewitt, was awoken by cries of “Murder!”, but domestic violence and shouts of that nature were common in the area and she ignored the noise. At 2:00 a.m., two other residents, husband and wife Joseph and Elizabeth Mahoney, returned to the Buildings and saw no one on the stairs. At the same time, the patrolling beat officer, PC Thomas Barrett, questioned a grenadier loitering nearby, who replied that he was waiting for a friend. At 3:30 a.m., resident Albert George Crow returned home after a night’s work as a cab driver and noticed Tabram’s body lying on a landing above the first flight of stairs. The landing was so dimly lit that he mistook her for a sleeping vagrant and it was not until just before 5:00 a.m. that a resident coming down the stairs on his way to work, dock labourer John Saunders Reeves, realized she was dead.

Mary Ann Nichols

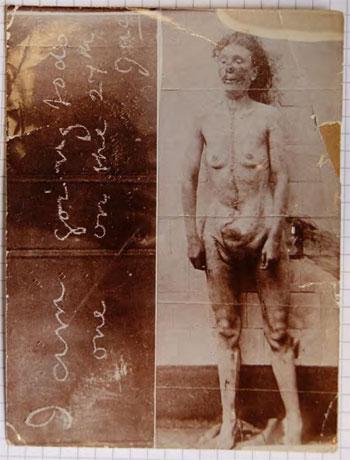

Mary Ann Nichols, commonly known as ‘Polly’, is widely regarded today as the first accepted victim of Jack the Ripper. She was born in Fetter Lane, near Fleet Street in the City of London in 1845 and in 1864 had married a printer, William Nichols, at St Bride’s Church. Together they had five children, but the marriage was troubled and in 1880 Mary Ann and William separated; he claimed it was due to her drinking, but Mary Ann’s father said that William had had an affair with the young midwife who had seen Mary Ann through the birth of her last child. Whatever the reason, Mary Ann was left to her own devices; William paid her a weekly allowance for her subsistence, but after hearing that she had got together with another man, he stopped her income. Polly fell into a life of degradation and for the next eight years she spent time in workhouses, infirmaries and was even arrested for vagrancy in Trafalgar Square in 1887. In 1888 she spent a brief time in the service of a wealthy family in Wandsworth, but this ended disastrously when she left unexpectedly, taking some clothes with her.

Eventually, Mary Ann found her way to the lodging houses of Spitalfields. She was 42 years of age, 5ft. 2in. tall with greying brown hair and a number of teeth missing from her upper and lower jaws. At first she lodged in Flower and Dean Street and then at 18 Thrawl Street, which is where she was staying on the last night of her life. At 12.30 a.m. on the morning of 31 August 1888, she was seen leaving the Frying Pan public house, at the corner of Thrawl Street and Brick Lane. By approximately 1.40 a.m. she had returned to the kitchen of 18 Thrawl Street, somewhat worse for drink. Unable to produce the required four pence for her bed, she was asked to leave, but she confidently said that she would soon get her doss money as she was wearing a “jolly bonnet”.

Just under an hour later, she was seen by Ellen Holland on the corner of Osborn Street and Whitechapel Road; Holland later said that Mary Ann was very drunk and had claimed to have had the money for her bed three times already that day, but had spent it all. The couple parted and Mary Ann walked eastward along Whitechapel Road.

At 3.40 a.m., her body was discovered by carman named Charles Cross near the entrance to a stable yard in Bucks Row, a quiet, dark street behind Whitechapel Underground Station. Cross was on his way to work when he saw what looked like a large piece of tarpaulin on the ground. As he got nearer he realised that it was a body lying on the ground. Whilst standing near the body, another man was walking past him. This was Robert Paul, who was himself on his way to work and was also a carman. Cross touched Paul on the shoulder as he passed him and asked him to look at what he had found. They both approached the body and saw that the woman’s clothes were in disarray. Upon touching her hands they realized that they were not entirely cold. Not knowing for sure whether she was dead or alive, and worried they were going to be late for work, they made their way west in the direction of Baker’s Row with the intention of informing the first policeman they found. On the corner of Hanbury Street and Baker’s Row they approached PC Jonas Mizen and told him of their discovery.

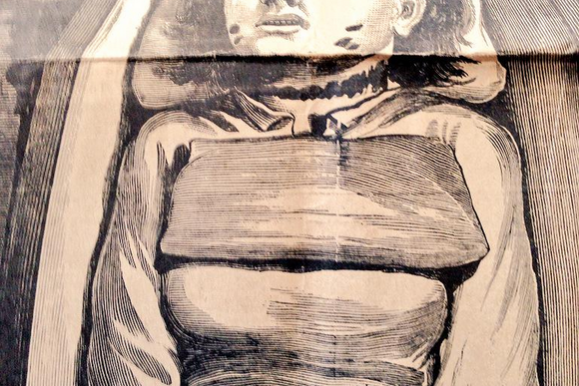

While Cross and Paul were telling PC Mizen of their gruesome discovery, PC John Neil was walking along Buck’s Row in the direction of Brady Street and noticed the body. He went to investigate, but he could not possibly have prepared himself for what he discovered. Mary Ann was lying on her back, her head was facing in an easterly direction, and her left hand was near to the stable yard gate. Her open hands were palm upwards and her legs were laid out and slightly apart. In the light of his policeman’s lamp, PC Neil could see that blood was oozing from a gash in the woman’s throat. He called to a passing constable, PC John Thain, to fetch Dr. Rees Llewellyn who was situated nearby at 152 Whitechapel Road. Having left Charles Cross and Robert Paul to go off to work, PC Mizen arrived and was immediately told to fetch the ambulance. In a short space of time, Dr. Llewellyn was present at the scene and pronounced life extinct. Under his orders, her lifeless body was taken by ambulance to the mortuary in Old Montague Street for closer inspection and it was here that further injuries, concealed by the woman’s clothing, were discovered. The throat had been cut twice, one incision going back to the spine. The abdomen had a long, jagged cut running from the centre of the bottom of the ribs down to the groin, and there were a number of other cuts and stabs to the lower abdomen. There were two small deep stab wounds to the vagina. There were also two bruises that were noticeable, one on the right lower jaw and the other on the left cheek, like the impression of a thumb print. The assumption was that the murder was carried out by a left-handed person due to the pattern of the wounds.

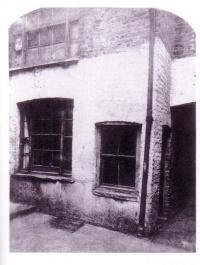

Durward Street. Whitechapel. The gateway is the location of where Polly Nichol’s was discovered on the 31st August 188

Mary Ann’s body was soon identified after the words ‘Lambeth Workhouse’ were found stencilled inside her petticoats. Inquiries at the workhouse brought forward a number of people who could put a name to the murdered woman and eventually William Nichols came forward to confirm the identity of his dead wife. As was customary, an inquest was convened, observed on behalf of the Metropolitan Police by Inspector Joseph Helson, divisional inspector of J- division (Bethnal Green) within whose jurisdiction the body was found. On the second day of the inquest, Helson was joined by a new, but most important figure in the story – Inspector Frederick Abberline.

Abberline had been a police officer for many years, having spent much of his time in service in Whitechapel. In 1887 he was transferred to central office at Scotland Yard, however following the murder of Mary Ann Nichols, he was brought back to his old stomping ground owing to his considerable knowledge of the East End. From here, Abberline would be in charge of the individual investigations into the murders of the women who would soon be considered the victims of one man. Significantly, the day after the murder, 1 September 1888, was also the first day in office for the new Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police CID, Dr Robert Anderson.

Unfortunately, Anderson, upon starting his new job, immediately left Britain on extended sick leave; it was regrettable that the man who, as head of CID, would be responsible for overseeing the Whitechapel murders case would not be present as events unfolded.

The inquest and press interviews with local residents also threw up further information about the night of the murder. Mrs Emma Green was a widow who lived at New Cottage with her three children. Even though they lived right next to the murder site, none of the family were woken in the night by any noise outside. Opposite was Essex Wharf where Walter Purkiss, the caretaker, was with his wife in the first-floor front bedroom. Again, neither heard any noises from Buck’s Row, even though Mrs Purkiss was awake much of the night. The only resident of the street who may have heard anything significant was Harriett Lilley of no.7 Buck’s Row who had heard a ‘painful moan’, followed a little later by whispering.

All this amounted to very little evidence and the murder remained a mystery, generating the usual inquest verdict of ‘murder against person or persons unknown.’ This time however, links were now being made between the death of Mary Ann Nichols and those of Emma Smith and Martha Tabram. The idea that criminal gangs were responsible for these terrible crimes was diminishing and even though the police were still looking into the movements of such gangs, the press had other ideas; the Star, a popular radical evening newspaper, claimed quite sensationally that this latest murder was “the third crime of a man who must be a maniac.”

No culprit was found, but attention began to veer towards the large number of eastern European Jews who had, during the previous decade, made Whitechapel their home after fleeing persecution and poverty in countries such as Russia and Poland. This part of the East End had a strong tradition of Jewish settlement and with its established communities and synagogues, as well as its convenient setting near the river, Whitechapel became the first point of entry into the United Kingdom for many. The Jewish population steadily grew throughout the 1880s and this brought its own problems, xenophobia being one. Resentment toward these displaced people had risen rapidly during that time and the Whitechapel murders created a spike in that resentment and as a result, the East End had a scapegoat for the horrors unfolding on the streets. Rumours quickly began to circulate about a Jewish slipper-maker with a reputation for ill-using prostitutes. Known only as ‘Leather Apron’, his profile began to grow as tale after tale of his sinister behaviour reached the press. The more sensational newspapers, in their turn, began to build him up as something to be feared, a “noiseless midnight terror” who lurked in the shadows and from whom no woman was safe. Despite the stories, ‘Leather Apron’ could not be traced. Would this murderer strike again?

Annie Chapman

It was about 6.00 a.m. on the morning of Saturday, 8 September 1888, when John Davis, one of seventeen residents of 29 Hanbury Street, descended the stairs of the house and opened the back door leading to the yard. He was about to leave for work and was no doubt going to use the outdoor privy before setting off. As the door swung open, below him, lying at the bottom of the stone steps leading to the back yard, was the mutilated body of a woman. She lay beside the fence that separated the yards of nos. 27 and 29 and her head was almost touching the steps; the abdomen had been opened up and over her shoulder was a pile of intestines. Around the neck was a deep jagged wound that almost severed the head from the body. This latest victim of the Whitechapel horrors was 47 year-old Annie Chapman, known to some as ‘Annie Sivvey’ or ‘Dark Annie’.

Annie Chapman was born Annie Eliza Smith in Paddington, London, in 1840. Like the three women who fell before her (and many of her class) she had a family, however a series of unfortunate and tragic events had conspired to put her in the squalid district of Spitalfields where she would ultimately meet her end. Annie had married John Chapman, a coachman, in 1869 and they had three children, two daughters and a son, the latter being born a cripple. The eldest daughter tragically died from meningitis aged twelve. Owing to John’s work, they lived in many affluent parts of west London, as well as Clewer in Windsor and it was whilst at the latter that Annie left the family around 1885 on account of her excessive drinking and the behaviour that resulted from it. It is possible that John was a heavy drinker too and the 10 shillings he paid Annie weekly following their separation stopped when he died of cirrhosis of the liver and dropsy on Christmas day 1886. By this time, she had been living with a sieve-maker named John Sivvey (which may be where she got her nickname from), but he left her soon after he husband’s death, perhaps after the money dried up. According to one friend, Annie appeared to be very affected by John’s death and “seemed to have given away all together.”

By the spring of 1888, Annie had begun living at a doss-house in Dorset Street, Spitalfields, known as Crossingham’s. She began a relationship of sorts with a man called Edward Stanley, known as ‘The Pensioner’ and they often spent weekends together at Crossingham’s, their bed paid for by Stanley. Since the death of her husband, Annie had obviously fallen on hard times; in mid-late August 1888, she had bumped into her younger brother, Fountain Smith, and had asked for money and whereas before she supported herself with a combination of John’s money and crochet-work, it appears she now had to resort to casual prostitution to make ends meet.

At some time in the first days of September, Annie got into a fight with fellow lodger Eliza Cooper; some accounts say it was over the attentions of Edward Stanley, others say it was over a bar of soap and the place where the fight took place was variously given as in Crossingham’s itself or the Britannia pub at the corner of Dorset Street and Commercial Street. Whatever the case, Annie received several bruises to the chest and a black eye. She was beginning to feel unwell and such injuries would not have helped her condition. This much was obvious when she met a friend, Amelia Palmer, near Christ Church the evening before her death. Annie complained of feeling ill and had been to the infirmary where they had given her some pills; she appeared world-weary, but knew what she had to do, saying “it’s no good my giving way. I must pull myself together and go out and get some money or I shall have no lodgings”.

A little later that evening , she was seen in the kitchen of Crossingham’s by several people. Annie appeared to be attempting to linger there for some time before getting the money to pay for her bed. Witnesses saw her take out a box of pills which promptly broke and she had to use a scrap of envelope to keep them in. At about 1.35 a.m., the deputy of Crossingham’s, Timothy Donovan approached Annie for her bed money, but she had none. After asking Donovan to reserve her regular bed, she promised to get the money and left by the side door. She was seen walking in the direction of Brushfield Street. Tragically, Annie would never return, but instead would be found in the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street having been mutilated in the most horrific manner.

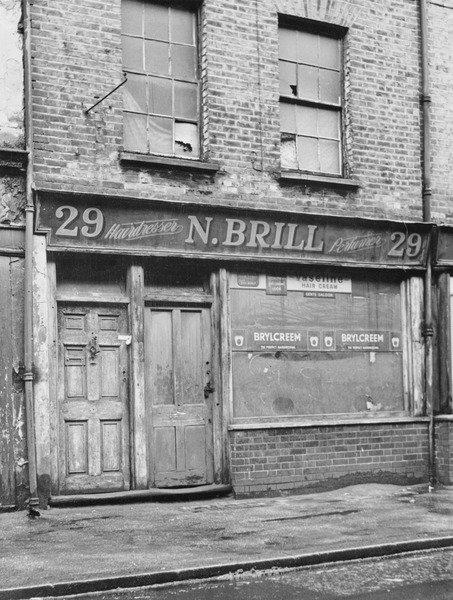

29 Hanbury Street London E1. Annie Chapman’s lifeless body was discovered in the back yard on the 8th September 1888

Obviously shocked and appalled by what he had discovered that morning, John Davis hurriedly ran out into Hanbury Street and came across a man by the name of Henry Holland who was on his way to work. Nearby were two men, James Green and James Kent, who were standing outside the Black Swan pub at 23 Hanbury Street. Davis shouted “Men, come here! Here’s a sight, a woman must have been murdered!” On seeing the body for themselves, the men spread out looking for assistance; at the end of Hanbury Street was Inspector Joseph Chandler who accompanied the men back to no. 29. Chandler immediately sealed off the passageway that led from the front of the house to the back yard and sent for reinforcements and the divisional surgeon, Dr. George Bagster Phillips, who lived at Spital Square close by.

In his initial examination of Annie’s corpse, Dr. Phillips noted the obvious injuries to her body, as well as the bruising to her chest and eye that she had sustained a few days earlier. Removed from, but still attached to her body and placed over her right shoulder were her small intestines and a flap of her abdomen. Two other portions of the abdomen and pubes were placed above her left shoulder in a large quantity of blood. The uterus, the upper part of the vagina and the greater part of the bladder had been removed and were missing. There were also abrasions on the fingers which indicated that rings had been forcibly removed from them. Dr Phillips also noted that despite the massive injuries to her neck and torso, there was not a significant amount of blood loss from the body, and that her tongue was left protruding from her swollen head, indicating that she was strangled before being mutilated.

The style of Annie’s murder was comparable to that of Mary Ann Nichols, eight days before. Dr. Philips did not give too much away at the inquest regarding the injuries to Annie Chapman, but his findings were published in the esteemed medical journal, The Lancet, a few weeks later. He stated that the murderer would have had to possess some form of medical or anatomical knowledge: “Obviously the work was that of an expert – of one, at least, who had such knowledge of anatomical or pathological examinations as to be enabled to secure the pelvic organs with one sweep of a knife.” The autopsy also revealed the reasons for Annie’s apparent illness; she was suffering from advanced disease of the lungs which had begun to affect the membranes of the brain, in other words, she was already terminally ill.

The inquest, as always, generated new information and brought forward more witnesses. A piece of leather apron was found in the backyard, leading to a minor flurry of sensation in that it was somehow linked to the mysterious ‘Leather Apron’ character, now very much in the public eye. It was soon ascertained that this strangely alarming item had no genuine significance as it was owned by Amelia Richardson, a resident who ran her own packing case business from the house. Testimony from her son, John, was rather more interesting as, being in the habit of checking the security of the cellar doors (in the back yard) following an earlier burglary, he had sat on the steps leading from the back door at 4.45 a.m. that morning and had seen nothing. He also commented that it was already getting light.

The Back Yard of 29 Hanbury Street. Annie Chapman’s body was discovered between the step and the fence.

One very important witness who came forward was Elizabeth Long, who worked at Spitalfields Market. She believed she had seen Annie outside 29 Hanbury Street talking to a man whom she described as being about 40 years old, wearing a dark coat and a deerstalker hat. He was described as foreign-looking and was of a “shabby genteel” appearance. Mrs Long stated that she heard the man say “will you?” to which Annie responded with the word “yes.” This incident apparently happened at about 5.30 a.m., around the same time that a resident of no. 27, Albert Cadosch, was venturing into his backyard. From the other side of the fence that separated the two yards, Cadosch believed he heard some people talking; he heard a woman’s voice say “no.” A short while later, he heard what he thought was something hitting the other side of the fence. It is more than possible that Albert Cadosch heard the murder of Annie Chapman taking place, but was so used to hearing people and noises in the back yard of no. 29 at all hours that he did not really give it much attention.

Such was the kind of vague testimony the police and public were subjected to. Again, the murderer of Annie Chapman, like before, was not apprehended, leading to a tidal wave of anger, frustration and sheer panic amongst the East End community. Newspaper reports spoke of outbreaks of unrest in the area and innocent men being targeted as ‘Leather Apron’, resulting in the police having to concern themselves with keeping the peace with alarming frequency. Despite their problems, there was a brief glimmer of hope when, on 10 September, Sergeant William Thick went to the Whitechapel home of John Pizer, a Jewish slipper-maker, and arrested him on suspicion of Annie Chapman’s murder, and of being ‘Leather Apron’ himself. Unfortunately, Pizer, despite being a person of interest to the police for some time, could qualify his whereabouts on the nights of the murders of both Nichols and Chapman and was therefore exonerated. Things were not going the way the authorities would have wished. The sensational newspapers summed up the situation in outlandish terms:

“London lies today under the spell of a great terror. A nameless reprobate – half beast, half man – is at large, who is daily gratifying his murderous instincts on the most miserable and defenceless classes of the community… Hideous malice, deadly cunning, insatiable thirst for blood – all these are the marks of the mad homicide. The ghoul-like creature who stalks through the streets of London, stalking down his victim like a Pawnee Indian, is simply drunk with blood, and he will have more.”

In mid-September, in the absence of Dr Robert Anderson, Chief Inspector Donald Swanson was given the important task of overseeing all information regarding the Whitechapel murders. A well-respected officer, Swanson was authorised by Metropolitan Police Chief Commisioner Charles Warren to be the Commissioner’s “eyes and ears” and that he be “acquainted with every detail… He must have a room to himself, and every paper, every document, every report, every telegram must pass through his hands. He must be consulted on every source.” As a result, the importance of Swanson in this case cannot be overemphasised and it could be argued that his knowledge of these most unique crimes would exceed that of almost any other officer. Inspector Abberline, who joined the hunt for the Ripper shortly before, has traditionally been given the honour of being the officer in overall charge of the case, however that role really fell to Swanson, and his undoubted experience would lead to his comments about the murders, and even the identity of the killer himself, being regarded very seriously in later years.

Elizabeth Stride

The murder of Annie Chapman marked the point where these East End murders became a great sensation. The newspapers were full of theories and reports about potential arrests and incidents that were immediately seized upon as being related to the ‘Whitechapel monster’. But this chaotic scenario was about to move up a gear when, on 27 September 1888, the Central News Agency received a letter, allegedly from the murderer himself. Written in red ink, for reasons that were explained, it read:

“25 Sept 1888

Dear Boss,

I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet. I have laughed when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some of the proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I cant use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope ha. ha. The next job I do I shall clip the ladys ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly wouldn’t you. Keep this letter back till I do a bit more work, then give it out straight. My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance. Good Luck.

Yours truly

Jack the Ripper

Dont mind me giving the trade name”

Written at right-angles to the main text was a further message, written in pencil:

“PS Wasn’t good enough to post this before I got all the red ink off my hands curse it No luck yet. They say I’m a doctor now. ha ha “

The letter was sent two days later to the Metropolitan Police, with a covering letter suggesting that it was a hoax. The police, it seems, took some notice of the content and duly kept the letter out of the public gaze until the murderer had indeed done “a bit more work.” That moment was not a long time in coming. The next in the series of Whitechapel murders occurred in the early hours of 30 September 1888, less than three weeks after the brutal death of Annie Chapman. Two women were killed within an hour of each other and in two very different locations; it would later be hailed in Ripper folklore as the ‘Double Event’.

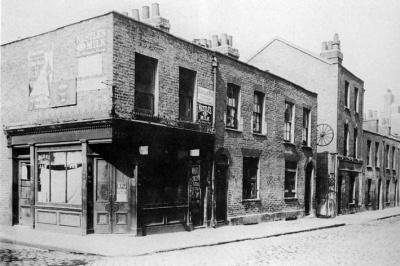

Berener Street. The entrance to Dutfields Yard can be seen beneath the wagon wheel. It was here that Elizabeth Stride’s body was discovered at 1am by Louis Deimshutz.

The first victim that night was Elizabeth Stride, commonly known as ‘Long Liz’. Born Elizabeth Gustafsdottir in 1843 in Stora Tumlehead, on the Western Coast of Sweden, she had been registered by the Gothenburg police for being a professional prostitute by the age of twenty-two. She was plagued by venereal infections and gave birth to a stillborn daughter in 1865, not long after the death of her mother. With money she inherited from her mother, she managed to immigrate to London in 1866 and settled in the Whitechapel District. Her troubled life appeared to be on the mend once she married John Stride in 1869, however thanks to her deplorable drinking habits and her ever-so -common brushes with the law for being drunk and disorderly, the couple separated in 1881. John died three years later of heart disease at the sick asylum in Bromley.

Losing the support of her husband left Elizabeth with no sufficient source of income and she obviously returned to her illicit ways in order to support herself. Having resorted to prostitution, Elizabeth found it extremely difficult to escape the clutches of the life of an unfortunate. She took to the temporary and affordable accommodation that the common lodging houses in the area offered. She lived in Brick Lane around December 1881, but spent the Christmas and New Year in the Whitechapel Infirmary, suffering with bronchitis. After moving from Brick Lane, Elizabeth stayed at a common lodging house at 32 Flower and Dean Street and remained there until 1885, when she met Michael Kidney, a waterside Labourer. They soon took up residence together at 38 Devonshire Street, Commercial Road, but their relationship was a far from happy one; they quarrelled often and frequently separated until, on the 25 September 1888, Elizabeth left Kidney for the last time and returned to her old lodgings in Flower and Dean Street. In the year 1887-8, she had accumulated eight convictions for drunkenness at Thames Magistrate’s Court.

On 29 September 1888, Elizabeth had been cleaning rooms in the lodging house during the day, earning a small wage of 6d. At 6.30 p.m. she stopped at the Queen’s Head public house on the corner of Commercial Street and Fashion Street and shortly after quenching her thirst, she made her way back to Flower and Dean Street in the company of Elizabeth Tanner in order to get herself ready for the evening ahead. Her subsequent movements were well documented.

Fellow resident Catherine Lane, a charwoman, stated that she saw Elizabeth between the hours of 7.00 and 8.00 p.m. that evening in the lodging house kitchen; as Elizabeth left, it was noted that she was wearing a long Jacket and black hat and appeared relatively sober. Charles Preston, a barber, stated that he too saw Elizabeth in the kitchen on that evening. He lent her his clothes brush as she was preparing to go out and wanted to smarten herself up. He said that she was wearing a black jacket trimmed with fur and a coloured striped silk handkerchief round her neck. Several hours later, John Gardner and John Best saw Elizabeth leave the Bricklayers Arms in Settles Street shortly before 11.00 p.m. with a man whom they described as about 5 ft 5in tall, with a black moustache, weak, sandy eyelashes and wearing a morning suit and a billycock hat. Gardner and Best, noticing that the couple were sheltering briefly from a sudden downpour, joked around, saying “that’s Leather Apron getting round you” before Elizabeth and the man went off.

Mathew Packer, a fruiterer of 44 Berner Street said that he sold half a pound of black grapes to a young man about 25 to 30 years of age, who was accompanied by a woman dressed in a black frock and a jacket with fur round the bottom and a black crape bonnet. She was also wearing a flower in her jacket, resembling a geranium which was white outside and red inside. The man was about 5 ft. 7 in. tall wearing a long black coat which was buttoned up and a soft felt hat described as a kind of “Yankee” hat. He had broad shoulders and spoke rather quickly in a rough voice. Packer regrettably changed his story on a number of occasions, but later identified the woman as Elizabeth Stride in the St George-in-the-east mortuary.

At 11.45 p.m., William Marshall, a labourer who lived at 64 Berner Street, witnessed a man kissing Elizabeth Stride as they were standing near his lodgings. He heard the man say “You would say anything but your prayers.” He described the man as middle aged, wearing a round cap with a small peak, about 5 ft 6 in tall, rather stout in build, and decently dressed.

At about 12.30 a.m. PC William Smith was pounding his beat along Berner Street when he saw a man and a woman standing in the street opposite a narrow passageway known as Dutfield’s Yard. The man was about 5ft 7in tall, 28 years old, with a small dark moustache and a dark complexion. He was wearing a black diagonal cutaway coat, a hard felt hat, a white collar and tie and was carrying a parcel wrapped up in newspaper about 18 inches long and 6-8 inches wide. The woman was wearing a red flower pinned to her jacket, which PC Smith later recognised at the mortuary when he went to view Elizabeth Stride’s body.

At 12.40 a.m. Morris Eagle, a member of the International Working Men’s Educational Club, stated that he passed down Dutfield’s Yard, which was adjacent to the club, and had seen nothing unusual; the club, which had only just finished presenting a lecture, was attended by a number of members who were now singing songs. Only five minutes later, the most significant witness of the night (and perhaps in the whole case), Israel Schwartz, had a most dramatic encounter.

Schwartz, a young Hungarian who spoke no English, was returning home to nearby Helen Street and was walking along Berner Street from Commercial Road. He saw a man stop and speak to a woman who was standing in the gateway of Dutfield’s Yard when suddenly the man tried to pull the woman into the street, throwing her down onto the pavement at which he woman cried out three times, but not very loudly. Schwartz, perhaps wishing to avoid getting involved in the incident, crossed to the other side of the road whereupon he noticed another man standing in the doorway of a pub at the corner of Berner and Fairclough Street who appeared to be in the act of lighting a pipe. The man who threw the woman down called out “Lipski” and with that, Schwartz walked away from the scene, but finding that he was followed by the second man he ran as far as the railway arches at the bottom of Berner Street but his pursuer had given up before he got that far.

Schwartz stated that the man he saw attacking Elizabeth Stride was about 5 ft. 5 in. tall, 30 years old with a fair complexion, dark hair, a small brown moustache, full face and broad shoulders, wearing a dark jacket, dark trousers and a black cap with a peak. The man smoking the pipe was described as 5 ft. 11in. tall, 35 years old, with a fresh complexion, light brown hair and a brown moustache. He wore a dark overcoat and an old black hard felt hat with a wide brim.

At 1.00 a.m., Louis Diemshutz returned with his horse and cart to his residence at the International Working Men’s Educational Club. He had been working that day at Westow Hill market, in Crystal Palace, where he sold costume jewellery from his barrow. He was also the steward of the club which he ran with his wife. As he turned into the gateway of Dutfield’s Yard, his horse shied to the left, causing Diemshutz to glance down at the ground next to the club wall to see what the matter was. He saw that there was something there, so he got off his cart and struck a match to illuminate the scene to get a closer look. The wind instantly snuffed out the match, so he ran in to the club to fetch a candle as he had seen what he thought was a drunken woman laying on the ground.

Diemshutz went back outside, joined by a few club members. As they approached the body they could see blood. They estimated that about two quarts of blood had coagulated upon the cobbles directly by the body from the neck. The men immediately went in search of a policeman, running in different directions and shouting as they went. As Diemshutz and company were frantically searching the streets for help, Morris Eagle managed to find assistance in the form of PCs Lamb and Collins in Commercial Road. Without hesitation, they returned to Dutfield’s Yard where they saw a crowd of people already gathering at the gateway to the yard. PC Lamb managed to keep them back, telling them that if they got blood on their clothes, then they would only attract trouble for themselves.

PC Lamb touched the woman’s face; it was still slightly warm. He could see that the blood by the body was still in a liquid state, however, he felt for a pulse but found nothing. Dr Frederick Blackwell was summoned to the scene from his home at 100 Commercial Road, but as Dr Blackwell was not dressed, his assistant Edward Johnston went on ahead of him. He stated that the body was all warm when he arrived – except for the hands which were quite cold – and that the blood had stopped coming out of the neck wound.

Dr Blackwell arrived at 1.16 a.m, according to his pocket watch. He reported that

The deceased was lying on her left side obliquely across the passage, her face looking towards the right wall. Her legs were drawn up, her feet close against the wall of the right side of the passage. Her head was resting beyond the carriage-wheel rut, the neck lying over the rut. Her feet were three yards from the gateway. Her dress was unfastened at the neck. The neck and chest were quite warm, as were also the legs, and the face was slightly warm. The hands were cold. The right hand was open and on the chest, and was smeared with blood. The left hand, lying on the ground, was partially closed, and contained a small packet of cachous wrapped in tissue paper. There were no rings, nor marks of rings, on her hands. The appearance of the face was quite placid. The mouth was slightly open. The deceased had round her neck a check silk scarf, the bow of which was turned to the left and pulled very tight. In the neck there was a long incision which exactly corresponded with the lower border of the scarf. The border was slightly frayed, as if by a sharp knife. The incision in the neck commenced on the left side, 2 ½ inches below the angle of the jaw, and almost in a direct line with it, nearly severing the vessels on that side, cutting the windpipe completely in two, and terminating on the opposite side 1 ½ inches below the angle of the right jaw, but without severing the vessels on that side. I could not ascertain whether the bloody hand had been moved. The blood was running down the gutter into the drain in the opposite direction of the feet. There was about 1lb. of clotted blood close by the body, and a stream all the way from there to the back door of the club.

Dr George Bagster Phillips was also alerted and arrived on the scene at approximately 2 a.m. and agreed with Dr Blackwell’s account. At 4.30 a.m., amidst growing excitement in the area, the body of Elizabeth Stride was taken to the small St George-in-the-east mortuary. At the time of her death she was described as being about 42 years old, 5ft 2 in. tall, with dark brown curly hair and a pale complexion. Her eyes were seen to be light grey and some of her upper front teeth were missing. Elizabeth’s clothing consisted of a long black jacket trimmed with black fur, an old skirt, a dark-brown velvet bodice, two light serge petticoats, a white chemise, a pair of white stockings, a pair of side-spring boots and a black crape bonnet.

Israel Schwartz’s account of the attack on the woman he later identified as being Elizabeth Stride, and his description of the man attacking her only fifteen minutes before she was found dead, was an important lead. Coupled with Dr. Blackwell’s opinion that death occurred between 12.46 a.m. and 12.56 a.m., it is highly probable that this was the man who killed her. It was also widely felt that, because Stride’s body exhibited none of the abdominal mutilations evident in the previous cases, the murderer may well have been disturbed by the arrival of Louis Diemschutz on his pony and cart.

Another element of Israel Schwartz’s statement is also interesting, namely the part where he says that the would-be attacker called out “Lipski!” According to Inspector Abberline, ‘Lipski’ had locally become an abusive term for the Jews since the arrest and subsequent suicide of Israel Lipski, a Jew who had been accused of murdering Miriam Angel in nearby Batty Street the previous year. Schwartz was described in the press as ‘semitic’ in appearance, leading to the possibility that the man’s outburst was aimed at him. Interestingly, Chief Inspector Donald Swanson, in whose hand Schwartz’s statement was written, made a side-note to the effect that he believed that the use of this word suggested that Stride’s attacker was Jewish.

What is unusual about Israel Schwartz’s experience is that he was never called to the inquest to give his evidence. As was often the case, some information regarding events surrounding these murders was picked up by the newspapers alone, when journalists sought out possible stories and apart from Swanson’s report in the official files, the other important version of Schwartz’s story appeared in the Star newspaper. Matthew Packer, the fruiterer who claimed to have sold grapes to Stride and a man that morning, was not called to the inquest probably because he kept changing his story and was therefore considered unreliable. Schwartz, however, had an important story to tell and regardless of how it was covered, his claims would have considerable influence on the hunt for the Ripper in years to come.

But that night, 30 September 1888, would see a second murder, so far the most violent in the series, acted out in the City of London. Had the arrival of Louis Diemschutz stopped the Whitechapel murderer in the act and so left his thirst for blood unsatisfied, driving him to kill again and with renewed ferocity?

Catherine Eddowes

At about the same time that Elizabeth Stride’s body was discovered in Berner Street, 46 year-old Catherine Eddowes was being released from Bishopsgate Police Station in the City of London. At 8.30 p.m. the previous evening she had been found slumped in front of 29 Aldgate High Street in a very drunken, but still conscious, state. A small crowd had assembled around her which attracted the attention of City Police Constable Louis Robinson. In vain, he tried to prop Catherine up against the front of No.29, as she immediately slumped back down again. When he asked her name, she merely replied “nothing.” PC Robinson was soon joined by PC George Simmons and together they lifted Catherine up and escorted her, perhaps with some difficulty, to Bishopsgate Police Station.

On reaching the station, Sergeant James Byfield, who was on desk duty that night, booked Catherine in and she was taken to a cell in order to sleep off her drunken stupor. Throughout the remainder of the night, PC George Hutt made regular checks on the cell at 12.55 a.m., after hearing Catherine singing quietly to herself, he checked for one last time. He felt that she was now sober enough to be released. Before leaving, she was asked her name and said that she was ‘Mary Ann Kelly’ who lived a 6 Fashion Street. She also asked the time at which PC Hutt told her that it was too late to get any more drink. Catherine muttered that she would get “a damn fine hiding” when she got home and PC Hutt responded with something resembling a reprimand; “And serve you right, you have no right to get drunk.” By the time she was released into the street, it was 1.00 a.m.; PC Hutt asked Catherine to pull the door to on her way out and as she did so she said “Good night old Cock” and was seen to turn in the direction of Houndsditch. Forty-five minutes later, she was dead, the next victim of the Whitechapel murderer.

The events surrounding the night of the ‘double event’, provides a key to the entire story set out in this book. Importantly, the murder of Catherine Eddowes, the most violent in the series so far, retains a huge significance in this context and therefore it is important to look at her life and the events leading to her death in greater detail.

She was born on 14 April 1842 in Graisely Green, Wolverhampton, to George Eddowes, a tin plate worker, and his wife Catherine and was the sixth child of twelve. By the time young Catherine was two years old, the family had made the big decision to move to London and settled in Bermondsey, one of several impoverished neighbourhoods south of the river Thames. Catherine was educated at St John’s Charity School there but tragedy soon struck when her mother died in 1855, followed by her father two years later. The children, now orphans, went their separate ways, many going to the Bermondsey Workhouse, but Catherine returned to Wolverhampton and stayed with an aunt, finding employment as a tin-plate stamper, a job she may have obtained through family connections. By the early 1860s, she had begun a relationship with a man named Thomas Conway who drew a pension from the 18th Royal Irish Regiment. Together they eked out a living around the midlands, often selling cheap ‘chap-books’ written by Conway, the content of which usually consisted of little histories, nursery rhymes or accounts of current events. Ironically, one of their booklets was a ballad commemorating the execution of Catherine’s cousin, Christopher Robinson, which was sold amongst the crowds gathered for his hanging for the murder of his fiancée in 1866.

Mitre Square. It was in the far left corner where the body of Catherine Eddowes was discovered at 1.45am by PC Watkins. It was here that the shawl was also discovered.

In 1863, Thomas and Catherine’s first child, Catherine Anne (known as ‘Annie’) Conway was born in Norfolk where Thomas was employed as a labourer. By 1868, the family had moved to London, taking lodgings in Westminster and by this time Catherine was using the surname Conway, a common enough thing to do when a couple were living as man and wife. She even had his initials crudely tattooed on her arm, but there is no record that the couple ever married. It was at Westminster that their second child, Thomas, was born. Continually on the move, the Conways gravitated back to Southwark where their last child, Alfred was born in 1873. By now, things were not going too well and Catherine’s growing predilection for alcohol had become an issue, as had Thomas’ occasional violent behaviour towards her. At Christmas 1877, Catherine’s older sister Emma met her for the last time and noted that she was sporting a black eye. With such problems mounting, the inevitable happened and Catherine and Thomas separated in 1881.

Another older sister of Catherine’s, Eliza Gold, lived in Spitalfields and Catherine followed suit, soon settling in Cooney’s common lodging house at 55 Flower and Dean Street, where she began a relationship with a labourer named John Kelly. They were to remain as a couple at the lodging house for the rest of her life. It appears that their relationship was a generally harmonious one, John later telling the press that they always got along well and rarely had a cross word. Soon after, Catherine became a grandmother when daughter Annie gave birth to a son, Louis, however, despite living not too far away in Bermondsey, Annie’s relationship with her parents was fraught. Thomas had come to stay with her at one time and had left on bad terms and Catherine’s regular visits to borrow money resulted in Annie and her family moving house without telling her mother of her new address.

During September 1888, Catherine and John Kelly, now well and truly a couple of long-standing, decided to take advantage of the common pursuit of ‘hopping’; this was a very popular escape from the grime of the city when, every year, many families from the poorer districts of London would go to Kent to pick hops whereby they would be able to earn some money and benefit from the cleaner air of the great outdoors. Unfortunately, bad weather throughout that summer ensured a poor crop and soon the couple, along with many others in their situation, were forced to make the long walk back from Kent to London. As Catherine and John did so, they struck up a friendship with a Mrs Emily Burrell and her partner, who were on their way to Cheltenham. Mrs Burrell gave Catherine a pawn ticket for a man’s shirt which would have been no use to them as they were not going to London themselves.

On reaching London on 27 September, weary and footsore, Catherine and John went their separate ways for the night – John stayed at 52 Flower and Dean Street and Catherine went to the casual ward in Shoe Lane, in the City of London. When she left the following morning, she allegedly said that she had returned to London “to earn the reward offered for the apprehension of the Whitechapel Murderer. I think I know him.” The superintendent of the ward warned her not to get herself killed, to which she replied “Oh, no fear of that.”

On the morning of 29 September, Catherine and John reunited, whereupon they went to Jones’ pawnbrokers near Christ Church Spitalfields and pawned a pair of John’s boots; with the 2 shillings and 6 pence they received, they bought some provisions and had breakfast in the kitchen at 55 Flower and Dean Street. The last time the couple were together was at about 2.00 p.m. that day in Houndsditch, by which time they appeared to be penniless again. John said he would find some casual work somewhere and Catherine revealed her intention of crossing the river to see her daughter and get some money from her. She never made it to Annie’s, but by 8.30 p.m. she had managed to get herself extremely drunk – where the money came from for this to happen is not clear, but prostitution could well have been one option, despite John Kelly later saying that he was not aware of Catherine ever having earned money through ‘immoral purposes’. And thus was Catherine Eddowes found slumped in a doorway in Aldgate High Street, arrested and placed in the cells at Bishopsgate police station.

Catherine’s release at 1.00 a.m. the following morning was charged with a tragic serendipity; being in the custody of the City police, she was allowed to go once she was deemed sober enough to look after herself, as was the City police policy in such cases. Had she been found drunk a short distance further east, she would probably have been found by a Metropolitan Police officer and taken to Leman Street or Commercial Street police station. It was Metropolitan Police policy to hold drunks until the following morning; if Catherine had entered this scenario, she would never have met her fate at the hands of the Whitechapel murderer. Forty five minutes after her release, Catherine’s brutally mutilated body was found in Mitre Square by City PC Edward Watkins.

PC Watkins’ beat usually took 15 minutes to cover. When he passed through Mitre Square at 1.30 a.m. there was nothing out of the ordinary to be seen and after completing his usual checks of alcoves and padlocks, he continued on his way. Yet at 1.44 a.m. he returned to the square and on turning into the dark, south-west corner, he found Catherine Eddowes’ body lying on the pavement. As he shone his lantern across his grisly discovery, he could see that the woman had been completely mutilated. He later told a reporter from the Daily News that

…her clothes were right up to her breast and the stomach was laid bare, with a dreadful gash from the pit of the stomach to the breast. On examining the body, I found the entrails cut out and laid round the throat, which had an awful gash in it, extending from ear to ear. In fact, the head was nearly severed from the body. Blood was everywhere to be seen. It was difficult to discern the injuries to the face for the quantity of blood which covered it. The murderer had inserted the knife just under the nose, cut the nose completely from the face, at the same time inflicting a dreadful gash down the right cheek to the angle of the jawbone. The nose was laid over on the check. A more dreadful sight I never saw; it quite knocked me over.

Watkins immediately ran across the square to the imposing Kearley and Tonge warehouse to seek help from the night-watchman there, George Morris, who happened to be a retired Metropolitan Policeman. On seeing the gruesome spectacle splayed across the pavement, Morris raced out of the square, through Mitre Street and into Aldgate, all the while blowing his old policeman’s whistle; believe it or not, City police officers did not possess whistles at that time! He managed to find PCs James Harvey and James Holland and they hurriedly followed him back to Mitre Square. PC Holland rushed to nearby Jewry Street to fetch Dr. George Sequeria, who arrived at the scene at 1.55 a.m. At the same time, Inspector Edward Collard at Bishopsgate Police Station received news of the murder and left for Mitre Square, after sending a constable to call on Dr. Frederick Gordon Brown, the City Police Surgeon, at Finsbury Circus. Arriving at the scene at approximately 2.18 a.m., Dr. Brown noted that several policemen were already in attendance along with Dr. Sequeira, but nobody had yet touched the body.

Dr. Brown’s report read thus:

The body was on its back, the head turned towards the left shoulder, the arms were by the side of the body, as if they had fallen there. Both palms were upwards and the fingers were slightly bent. A thimble was lying in the ground near the right hand, the clothes were drawn up above the abdomen, the left leg was extended straight down, in a line with the body, and the right leg was bent at the thigh and knee, there was great disfigurement to the face, the throat cut across, below the cut was a neckerchief, the upper part of the dress was pulled open a little way, the abdomen was all exposed, the intestines were drawn out to a large extent and placed over the right shoulder, they were smeared over with some feculent matter, a piece of about 2 feet was quite detached from the body and placed between the body and the left arm, apparently by design, the lobe and the auricle of the right ear was cut obliquely through, there was a quantity of clotted blood on the pavement on the left side of the neck, round the shoulder and upper part of the arm, and fluid blood coloured serum which had flowed under the neck to the right shoulder, the pavement sloping in that direction, the body was quite warm, no death stiffening had taken place, she must have been dead most likely within the half hour, we looked for superficial bruises and saw one, no blood on the skin of the abdomen or secretion of any kind on the thighs, no spurting of blood on the bricks or pavement around, no marks of blood below the middle of the body, several buttons were found in the clotted blood after the body was removed, there was no blood on the front of the clothes, there were no traces of recent connection.

A pencil sketch of the crime scene, with the body in situ, was also made before Catherine Eddowes was taken to the mortuary in Golden Lane. The face had been horrifically mutilated; a piece of her ear dropped from her clothing when she was undressed at the mortuary, her nose had been cut off and two inverted, “V”, cuts were evident under each eye. As if this was not enough, it was found that her left kidney and her uterus were missing. Dr. Brown later commented that someone who knew the position of the kidney must have done it. He further stated that the killer must have possessed, “a good deal of knowledge as to the position of the organs in the abdominal cavity and the way of removing them”.

A comprehensive list of Catherine’s clothing and belongings was made:

– Black Straw Bonnet trimmed with green & black Velvet and black beads, black strings.

– Black Cloth Jacket, imitation fur edging round collar, fur round sleeves…2 outside pockets, trimmed black silk braid & imitation fur.

– Chintz Skirt, 3 flounces, brown button on waistband.

– Brown Linsey Dress Bodice, black velvet collar, brown metal buttons down front.

– Grey Stuff Petticoat, white waist band.

– Very Old Green Alpaca Skirt.

– Very Old ragged Blue Skirt, red flounce, light twill lining.

– White Calico Chemise.

– Mans White Vest, button to match down front, 2 outside pockets.

– No Drawers or Stays.

– Pair of Mens lace up Boots, mohair laces. Right boot has been repaired with red thread.

– 1 piece of red gauze Silk…found on neck.

– 1 large White Handkerchief.

– 2 Unbleached Calico Pockets.

– 1 Blue Stripe Bed ticking Pocket, waist band, and strings.

– 1 White Cotton Pocket Handkerchief, red and white birds eye border.

– 1 pr. Brown ribbed Stockings, feet mended with white.

– 12 pieces of white Rag, some slightly bloodstained.

– 1 piece of white Coarse Linen.

– 1 piece of Blue & White Shining (3 cornered).

– 2 Small Blue Bed ticking Bags.

– 2 Short Clay Pipes (black).

– 1 Tin Box containing Tea.

– 1 do. do. do. Sugar.

– 1 Piece of Flannel & 6 pieces of soap.

– 1 Small Tooth Comb.

– 1 White Handle Table Knife & 1 metal Tea Spoon.

– 1 Red Leather Cigarette Case, white metal fittings.

– 1 Tin Match Box, empty.

– 1 piece of Red Flannel containing Pins & Needles.

– 1 Ball of Hemp.

– 1 piece of old White Apron.

Some press reports described the outer chintz skirt as having a pattern of chrysanthemums or Michaelmas daisies. The ‘old white apron’ was also described as being extremely dirty and a section of it was missing. This missing piece was found at 2.55 a.m. by PC Alfred Long lying in the open doorway leading to the staircase of 108-119 Wentworth Model Dwellings in Goulston Street, back over in Whitechapel. The piece of apron was bloodstained. As PC Long checked for any other signs of blood in the immediate area, he discovered some writing in chalk on the wall directly above where the apron piece had lain; it read “The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing”.

After searching the staircase and finding nothing else of any significance, he obtained the help of a fellow officer to guard the writing and headed, with the bloodied apron, for Commercial Street Police Station, arriving there at approximately 3.10 a.m. Shortly after this discovery, officers were alerted to the location from both the Metropolitan and City police. City detectives Daniel Halse and Baxter Hunt soon arrived at Goulston Street. Halse, along with Detective Sergeant Robert Outram and Detective Constable Edward Marriott had been standing near Mitre Square when the alarm had been raised and were at that time part of a sweep of the area following the reports of Elizabeth Stride’s murder. Halse took charge of guarding the graffiti and Hunt returned to Mitre Square. As other officers arrived in Goulston Street, it was generally felt by members of the City police that the writing should be photographed, however their Metropolitan counterparts were already beginning to feel uneasy about leaving the message on view. It was a Sunday morning and the thriving Petticoat Lane Market, of which Goulston Street was an offshoot, would soon be busy with both Jewish and Gentile traders and visitors. Metropolitan Superintendent Thomas Arnold was concerned that the message was inflammatory enough to spark a disturbance, particularly after the mass-panic associated with ‘Leather Apron’ previously and that it may be necessary to erase it. City officers pushed for the erasure of the problematical word ‘Juwes’ only, but as Goulston Street was not within their jurisdiction, it was not their decision to make.

The decision was made for them when, at 5.30 a.m., Chief Commissioner Charles Warren arrived at the scene and agreeing with Arnold’s concerns, had the writing erased in its entirety. It appears that by committing a murder within the City boundary, the Ripper, consciously or otherwise, had put a spanner in the works by bringing these two separate police forces together to investigate the same crimes.

Warren’s decision to erase the writing was a controversial one and remains so for students of the case today. There is no saying what might have happened had the ‘wrong’ person seen that message, but the deed was done. Of course there has been much debate over the significance of what has become known as the ‘Goulston Street Graffito’, with some believing the Ripper had written it and others feeling that, in an area populated by so many Jewish immigrants, such derogatory sounding graffiti would have been commonplace. Nonetheless, it was only one more sensational event on a night that was full of surprises. One such surprise was how the Ripper managed to perpetrate his crimes under extremely tight circumstances and as testimony from various witnesses came forward, the sheer daring of the Whitechapel murderer came into sharp focus.

As PC Watkins checked Mitre Square at 1.30 a.m. that morning, finding nothing out of the ordinary, three men, Joseph Lawende, Harry Harris and Joseph Hyam Levy, were preparing to leave the Imperial Club on Duke Street, close by Mitre Square. Having waited for a shower of rain to pass, they left a few minutes after 1.30 a.m. and began to walk along Duke Street toward Aldgate. As they passed the narrow entrance to Church Passage on the opposite side of the road (which led directly into Mitre Square), they noticed a man and a woman standing there. Levy, referring to the couple, said to Harris, “Look there, I don’t like going home by myself when I see those characters about.” Neither Harris nor Levy gave them any more consideration than that, but Lawende appears to have taken more notice. He described the man as “of shabby appearance, about 30 years of age and 5ft. 9in. in height, of fair complexion, having a small fair moustache, and wearing a red neckerchief and a cap with a peak.” It was also said that he had the appearance of a ‘sailor’. The woman was standing with her back to the three men and was wearing a black jacket and black bonnet. Later, Lawende was shown Catherine Eddowes’s clothing and believed it was the same he had seen worn by the woman. She appeared to be a little shorter than the man and she had her hand on his chest. The couple did not appear to be quarrelling or drunk. Lawende’s probable sighting of Catherine Eddowes with a man shortly before her death became the second potential sighting of the murderer (after Israel Schwartz) that night. Sadly, Lawende also went on to say that he did not feel he could recognize the man again if he were confronted with him.

This sighting took place at approximately 1.35 a.m. Five minutes later, PC James Harvey, the only other officer whose beat took him close to Mitre Square that night, passed along Church Passage from Duke Street. He did not see anybody near the passage at that time and as his beat did not require him to enter it, he stopped briefly at the entrance to Mitre Square. Having noticed nothing out of the ordinary, he turned round and went back the way he had come. It is very likely that as he did so, the murder of Catherine Eddowes was taking place in the corner of Mitre Square opposite, the lack of light in that corner giving the murderer excellent cover. Four minutes later, PC Watkins returned and found the body.

But it was not just PCs Watkins and Harvey who came into close proximity with the murder scene. George Morris, the watchman at the Kearley and Tonge warehouse, claimed that he had left the front door of the building open at the time the murder may have happened whilst he cleaned the stairs within. Off-duty City policeman Richard Pearce, who lived in one of two houses in Mitre Square, was sleeping in the bedroom with his family, none of whom heard any disturbance during the night. Similarly, George Clapp, sharing his home at 5 Mitre Street with his wife and a nurse who looked after Mrs Clapp, heard nothing unusual, even though their bedroom windows were just above the spot where the murder took place. And finally, James Blenkinsopp, a night-watchman looking after some road works in St James’ Place (connected to Mitre Square by a small passage) had nothing to report other than a well-dressed man apparently walking by at 1.30 a.m. asking him if he had seen a man and a woman pass through. It was as if the Ripper was a ghost. He managed to entice his victim into the square, perform his terrible act of brutal murder, position the body and viscera in a specific manner, steal parts of her body and slip away invisibly into the night within a timescale of 8-9 minutes, all in a corner which was very badly lit.

It took a while for the body of Catherine Eddowes to be identified. John Kelly had heard of the murder but sadly was unable to put two and two together until he read of the discovery of Mrs Burrell’s pawn ticket lying by Catherine’s body. After he identified the body, Catherine’s sister Eliza Gold also came forward. Thomas Conway, who by now was living in Westminster, came forward with his two sons to exonerate himself of any suspicion. The funeral, which took place on 8 October, was a great affair and was reported extensively in the newspapers and reaching the pages of the national press. The Daily Telegraph reported:

The procession left the mortuary shortly after half-past one o’clock. It consisted of a hearse of improved description, a mourning coach, containing relatives and friends of the deceased, and a brougham conveying representatives of the press. The coffin was of polished elm, with oak mouldings, and bore a plate with the inscription, in gold letters, “Catherine Eddowes, died Sept. 30, 1888, aged 43 [sic] years.” One of the sisters of the deceased laid a beautiful wreath on the coffin as it was placed in the hearse, and at the graveside a wreath of marguerites was added by a sympathetic kinswoman. The mourners were the four sisters of the murdered woman, Harriet Jones, Emma Eddowes, Eliza Gold, and Elizabeth Fisher, her two nieces Emma and Harriet Jones, and John Kelly, the man with whom she had lived. As the funeral procession passed through Golden-lane and Old-street the thousands of persons who followed it nearly into Whitechapel rendered locomotion extremely difficult. Order was, however, admirably maintained by a body of police under Superintendent Foster and Inspector Woollett of the City force, and beyond the boundaries of the City by a further contingent under Superintendent Hunt and Inspector Burnham of the G Division. The route taken after leaving Old-street was by way of Great Eastern-street, Commercial-street, Whitechapel-road, Mile-end-road, through Stratford to the City cemetery at Ilford. A large crowd had collected opposite the parish church of St. Mary.s, Whitechapel, to see the procession pass, and at the cemetery it was awaited by several hundreds, most of whom had apparently made their way thither from the East-end. Men and women of all ages, many of the latter carrying infants in their arms, gathered round the grave.

***

Importantly, Israel Schwartz and Joseph Lawende, by being in the right place at the right time, became, like Elizabeth Long following her sighting of Annie Chapman in Hanbury Street and perhaps PC William Smith in Berner Street, two individuals who may have set eyes on Jack the Ripper himself. Very little is known about Israel Schwartz other than he was a Hungarian who spoke hardly any English and who had “the appearance of being in the theatrical line”. He was certainly married by this time as it was stated that he and his wife had moved from their lodgings in Berner Street to a new address off Backchurch Lane nearby on the day of the incident. Joseph Lawende, a cigarette maker, was Polish and had come to Britain in about 1871, marrying in 1873; at his wedding, he anglicised his surname to Lavender, a title he would generally keep for the rest of his life.

What is significant about these two witnesses – over Mrs Long and PC Smith – is that both were Jewish, something that would prove of great importance when claims that the identity of Jack the Ripper was known were published many decades later. But for the moment at least, their value lay in the simple premise that one or both of them had seen the Whitechapel murderer.

The night of the ‘double event’, for all its horrors and excitement, signalled a cessation in the murders for several weeks, however the sensation was kept alive when the press finally published the ‘Dear Boss’ letter, at last bringing the famous name ‘Jack the Ripper’ to the attention of the public. The police continued to make their enquiries, interviewing thousands of people and distributing tens of thousands of leaflets to local households requesting information and assistance. Hundreds of arrests were made, without any positive result. The endeavours of the authorities were potentially boosted by the creation of ‘vigilance committees’, essentially groups of local businessmen who had got together after realising that the murders had begun to affect their livelihoods. Not only did they start a campaign to get the Metropolitan Police to offer rewards for the capture of the Ripper, but they also spent many a night being a visible presence on the streets after dark, essentially attempting to become the extra eyes and ears of the beleaguered police. The most prominent of these committees was the Mile End Vigilance Committee, whose president was Mile End painter and decorator George Lusk. With his name appearing in the newspapers often, Lusk became the target of some strange incidents, including the receipt of alleged letters from the murderer. The most famous of these arrived at his home on the evening of 16 October. The letter came with a parcel containing half a human kidney; it read:

From hell

Mr Lusk,

Sir

I send you half the Kidne I took from one woman and prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise. I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer

signed Catch me when you can Mishter Lusk

In light of the removal of a kidney from Catherine Eddowes only two weeks previously, it made the whole package highly contentious. Apart from being definitely human, medical experts at the time could not ascertain whether the kidney had even belonged to a woman, let alone Eddowes. Many rumours have since circulated about the piece of kidney, including the popular suggestion, put forward in memoirs and other studies, that it had traces of Bright’s disease, a condition that afflicted alcoholics, as did the organ remaining in Catherine Eddowes’ body. If we wish to go back to the original reports to check this claim, we have to remain frustrated as the organ was analysed several times, but the official reports or notes have long been lost.

This all amounted to a lot of frustration and again, no real leads to find a culprit. Many were angry that, despite the efforts of the vigilance committees, the Metropolitan Police were against the offering of rewards for the capture of the murderer as they felt that, from experience, the offer of money often brought out the time-wasters and hoaxers. The City of London, not bound by the decisions of the Home Office, did offer a reward which was bolstered by those offered by private individuals. The absence of Robert Anderson from his post as Assistant Commissioner CID was now being commented on unfavourably by the press and following the double murder, he finally returned from abroad to a Metropolitan Police force that was still powerless to capture the Whitechapel Murderer. On top of all this, the legend of ‘Jack the Ripper’ was in full swing as the publication of the ‘Dear Boss’ letter on 1 October effectively cemented the name into history. It was joined soon after by a postcard, written in the same hand, which mentioned the ‘double event’ as well as innumerable imitations; the authorities were deluged with Ripper letters, the one received by George Lusk being the most controversial.

The next Whitechapel murder would not take place until 9 November after a pause of five weeks. It outstripped everything that had come before in sheer brutality and on this occasion, the murderer made his mark in Spitalfields once again, at the heart of the East End’s most impoverished district.

Mary Jane Kelly

The fifth and, in my and many people’s minds, the final Ripper victim was Mary Jane Kelly. Her murder was the dramatic conclusion to the run of gruesome violence inflicted on a small group of prostitutes, murdered in the East End by the same killer. Mary’s body was, without doubt, the most brutally and viciously attacked. Her butchered remains were discovered in her lodgings at 13 Millers Court, Dorset Street, on the morning of 9 November 1888.

Mary Jane Kelly was a 25 year-old prostitute described as 5ft. 7in. tall, with a fair complexion, a rather stout build, blue eyes and a very fine head of hair. What we know about Mary’s background is contentious as it originates from Mary herself and was passed on to those who knew her, but even today, with so much access to genealogical databases, confirmation of the facts proves elusive. What follows is that story of her life, all, some, or none of which may be true.

She originated from Limerick, Ireland, and moved with her family to Carmarthenshire in Wales when she was very young. At the tender age of 16, she married a collier by the name of Davies, however fate was to strike a cruel blow to Mary, for her husband died tragically in a mining disaster within two years of their marriage. She apparently moved to Cardiff where, under the influence of a cousin, she became involved in prostitution. From thereon in, her life took an unusual turn. Moving to London by 1884, she became involved in an exclusive West End brothel and apparently travelled to France with a ‘gentleman’, however this was not the life for her and she returned to England. It has been suggested that the trip to France inspired Mary to occasionally call herself ‘Marie Jeannette’. Mary settled in the East End, near the London docks, living with a Mrs Buki, however Mary’s growing fondness for alcohol meant that she had to leave and she soon went to live at the home of a Mrs Carthy. In 1886, Mary left Mrs Carthy’s lodgings to live with a man in Stepney, however before long she was drawn to the doss-houses of Spitalfields.

On Good Friday 1887, she met a young man named Joseph Barnett and the two quickly made the decision to live together, which they did in various residences before finding a room in Dorset Street, Spitalfields. Room 13, Millers Court, was located at the end of a small passageway between 26 and 27 Dorset Street; it was actually the back room of no.26 which had been separated from the rest of the property using a false partition by the landlord, John McCarthy, who ran a chandlers shop from no.27. Mary and Joseph took up residence in early 1888, paying four shillings and six pence a week for the squalid little room.

Joseph Barnett supported the couple financially but lost his job as a Billingsgate fish porter in early August, which left Mary with no other option but to resort to prostitution. Along with Mary’s habit of allowing other prostitutes to sleep in the room, this caused Joseph to walk out on Mary on 30 October and take up residence in a lodging house in New Street, Bishopsgate. The couple had also run up 3 months rental arrears. The couple still appeared to be on good terms and Barnett had visited Mary between 7.00 and 8.00 p.m. on the evening of 8 November to apologise for not having any money to give her. But that was the last time her saw her alive.

That last night of Mary’s life threw up some interesting incidents. Mary Ann Cox lived at room 5 Miller’s Court and claimed to have known Mary Kelly for about 8 months. She had followed Mary, who was with a man, into Millers Court at about 11.45 p.m. on that Thursday night. The couple entered room13 and as Mary was walking through her door, Mrs. Cox said goodnight to her; Mary was very drunk and could scarcely answer, but managed to utter a slurred “good night.” The man who accompanied her was carrying a quart can of beer and was described as about 36 years old, about 5ft. 5in. tall, with blotches on his face, small side whiskers and a thick carroty moustache, dressed in shabby dark clothes, a dark overcoat and a dark felt hat. She went on to say that she soon heard Mary singing, “Only a violet I plucked from my mother’s grave”, a popular song of the time. Mrs. Cox was in and out of her room several times that evening and when she finally returned at 3.00 a.m. all was dark in room13 and she didn’t hear any noise for the rest of the night.

Elizabeth Prater lived at 20 Millers Court, a room above Mary’s. At about 3.30 or 4.00 a.m. she was awoken by her kitten and heard a cry of ‘murder’ in a female voice about two, or three times. As Dorset Street was considered the roughest in the area at the time, she was used to such cries and so she ignored them and went back to sleep, not waking until 11.00 a.m. Sarah Lewis, staying with friends at 2 Miller’s Court, may have heard the same cries at around the same time. Lewis, however, had another tale to tell. On her arrival at Miller’s Court, around 2.30 a.m., she saw a man standing over against the lodging house on the opposite side of the street to Millers Court. He was described as not tall but stout and had on a wide-awake black hat.

The man Sarah Lewis described was more than likely to have been George Hutchinson, a friend of Mary Kelly. He presented himself as a witness but not until the inquest into Mary’s death had been concluded, when he appeared at Commercial Street Police Station at 6.00 p.m. on 12 November 1888. He too had an interesting story to relate.

He stated that he was walking along Commercial Street, between Thrawl Street and Flower and Dean Street, at about 2.00 a.m. that morning when he was approached by Mary, who said, “Hutchinson, will you lend me sixpence?” He said that he didn’t have it to give her and Mary went on her way. She was heading back in the direction of Thrawl Street when a man coming in the opposite direction tapped her on the shoulder and said something to her, at which they both burst out laughing. Hutchinson said that he heard her say, “Alright”, to him and the man replied, “You will be alright for what I have told you.” He then placed his right hand around her shoulders. Hutchinson stood against the lamp of the Queen’s Head Public House at the corner of Fashion Street and watched as the couple came past him. The man dropped his head with his hat over his eyes, so Hutchinson stooped down to look him in the face, at which the man gave him a stern look in return. The couple headed into Dorset Street and Hutchinson followed. Mary and her ‘acquaintance’, stood at the entrance to Miller’s Court for a few minutes and the man said something to her to which Mary replied “Alright my dear, come along, you will comfortable.” The man then placed his arm around her shoulder and gave her a kiss and they both disappeared into the court together. Hutchinson stood on the other side of the road for about three quarters of an hour, during which time he was probably seen by Sarah Lewis. When he realised that neither Mary nor her companion were coming out any time soon, he went away.

Hutchinson gave a description of the man as aged about 34 or 35, height 5ft. 6in., with a pale complexion, dark eyes and eyelashes and a slight moustache, curled at the ends. He was wearing a long coat trimmed with astrakhan, with a dark jacket underneath, a light waistcoat, dark trousers, a dark felt hat turned down in the middle, button boots and gaiters with white buttons. He apparently wore a thick gold chain, a white linen collar and a black tie with a horse shoe pin, suggesting a certain degree of affluence. He was Jewish in appearance and walked “very sharp.” Hutchinson also noticed that he was carrying a small parcel with a strap around it.

At 10.45 a.m. that morning, John McCarthy sent his assistant, Thomas Bowyer, to try and collect some of the overdue rent from Mary. Bowyer went through the passageway to room13 and knocked on the door and despite several attempts, received no answer. The door appeared locked from the inside and rather than walking away empty handed, he went round to the side window, which had a broken pane, put his hand through the gap in the frame and pulled back the muslin curtain. In the gloom of that little room was the corpse of Mary Jane Kelly – she was lying on the bed and she had been literally ripped to pieces. Shocked by the sight, he immediately ran to fetch John McCarthy who, with Bowyer, swiftly ran to Commercial Street Police Station where they alerted Inspector Walter Beck and Sergeant Edward Badham to their discovery. After arriving at Millers Court and viewing the horrendous scene, Inspector Beck sent for assistance from Divisional Superintendent ThomasArnold and the division surgeon Dr. George Bagster Phillips.

Millers Court was sealed off to the public by 11.00 a.m. On his arrival, Dr. Bagster Phillips viewed the scene through the window and satisfied himself that the woman in the room required no immediate assistance. A decision was made to use bloodhounds and so a long wait ensued before the room could be opened; by 1.00 p.m. no bloodhounds had arrived and so, in the absence of a key, John McCarthy was ordered to break down the door of Mary’s room with a pickaxe. The scene that greeted those who entered that tiny room must have been more than most could bear, as Dr. Thomas Bond’s report made very clear: