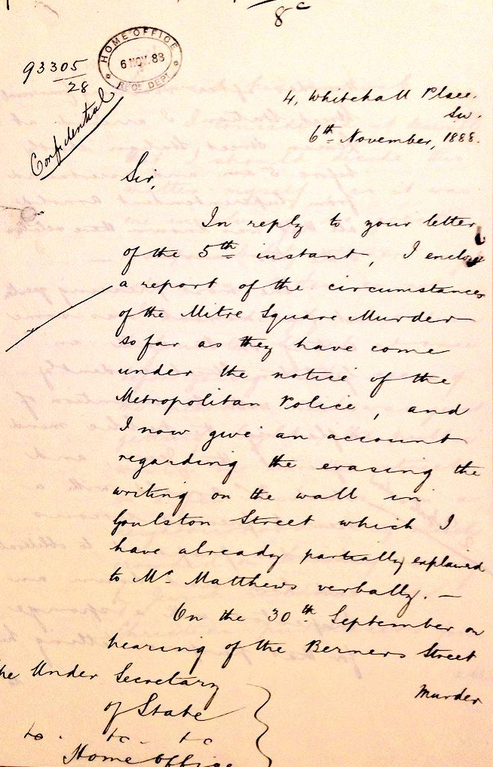

Warren’s Report to the Home Secretary

6 November 1888

4 Whitehall Place, S.W.

6th November 1888

Confidential

The Under Secretary of State

The Home Office

Sir,

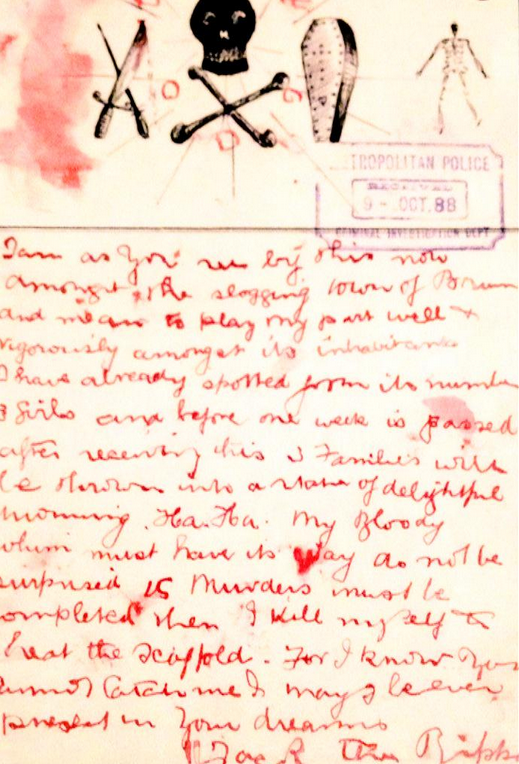

In reply to your letter of the 5th instant, I enclose a report of the circumstances of the Mitre Square Murder so far as they have come under the notice of the Metropolitan Police, and I now give an account regarding the erasing the writing on the wall in Goulston Street which I have already partially explained to Mr. Matthews verbally.

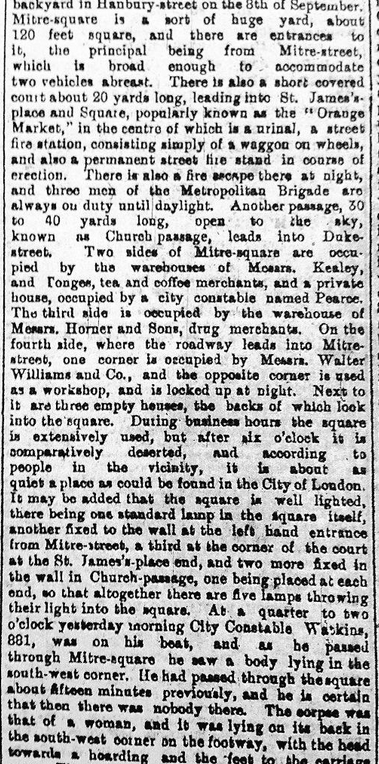

On the 30th September on hearing of the Berner Street murder, after visiting Commercial Street Station I arrived at Leman Street Station shortly before 5 A.M. and ascertained from the Superintendent Arnold all that was known their relative to the two murders.

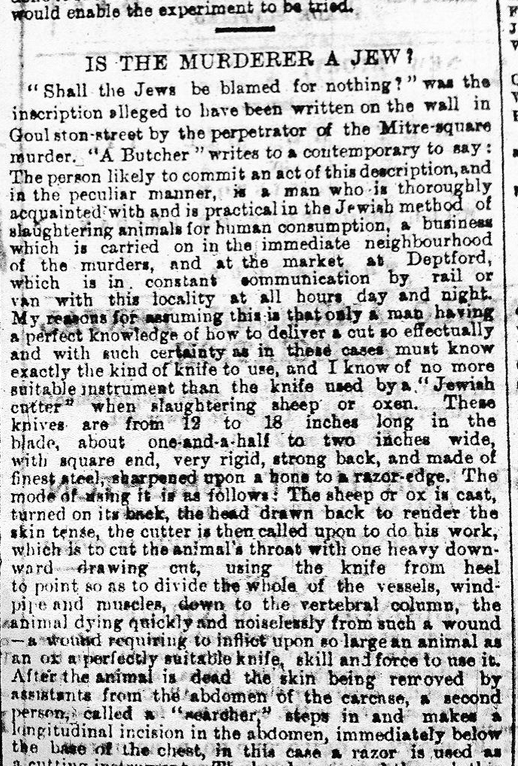

The most pressing question at that moment was some writing on the wall in Goulston Street evidently written with the intention of inflaming the public mind against the Jews, and which Mr. Arnold with a view to prevent serious disorder proposed to obliterate, and had sent down an Inspector with a sponge for that purpose, telling him to await his arrival.

I considered it desirable that I should decide the matter myself, as it was one involving so great a responsibility whether any action was taken or not.

I accordingly went down to Goulston Street at once before going to the scene of the murder: it was just getting light, the public would be in the streets in a few minutes, in a neighbourhood very much crowded on Sunday mornings by Jewish vendors and Christian purchasers from all parts of London.

There were several Police around the spot when I arrived, both Metropolitan and City.

The writing was on the jamb of the open archway or doorway visible in the street and could not be covered up without danger of the covering being torn off at once.

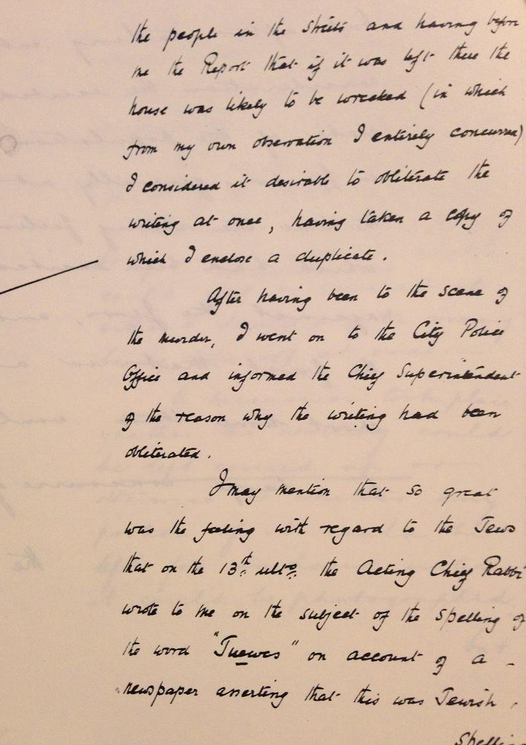

A discussion took place whether the writing could be left covered up or otherwise or whether any portion of it could be left for an hour until it could be photographed; but after taking into consideration the excited state of the population in London generally at the time, the strong feeling which had been excited against the Jews, and the fact that in a short time there would be a large concourse of the people in the streets, and having before me the Report that if it was left there the house was likely to be wrecked (in which from my own observation I entirely concurred) I considered it desirable to obliterate the writing at once, having taken a copy of which I enclose a duplicate.

After having been to the scene of the murder, I went on to the City Police Office and informed the Chief Superintendent of the reason why the writing had been obliterated.

I may mention that so great was the feeling with regard to the Jews that on the 13th. the Acting Chief Rabbi wrote to me on the subject of the spelling of the word “Jewes” on account of a newspaper asserting that this was Jewish spelling in the Yiddish dialect. He added “in the present state of excitement it is dangerous to the safety of the poor Jews in the East [End] to allow such an assertion to remain uncontradicted. My community keenly appreciates your humane and vigilant action during this critical time.”

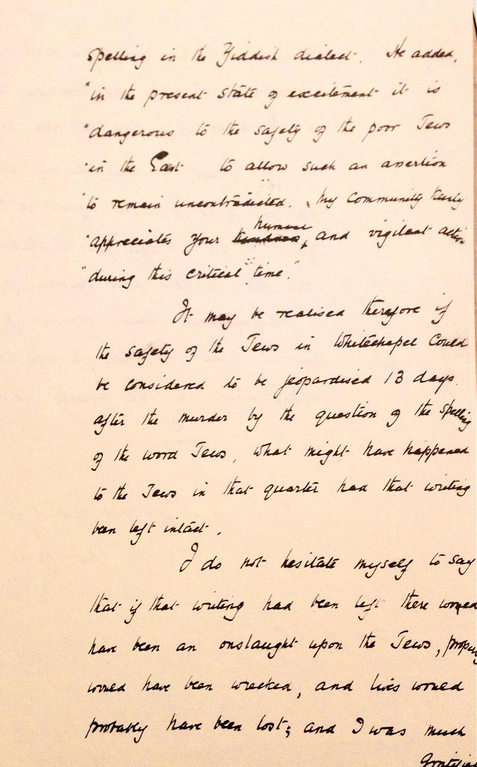

It may be realised therefore if the safety of the Jews in Whitechapel could be considered to be jeopardised 13 days after the murder by the question of the spelling of the word Jews, what might have happened to the Jews in that quarter had that writing been left intact.

I do not hesitate myself to say that if that writing had been left there would have been an onslaught upon the Jews, property would have been wrecked, and lives would probably have been lost; and I was much gratified with the promptitude with which Superintendent Arnold was prepared to act in the matter if I had not been there.

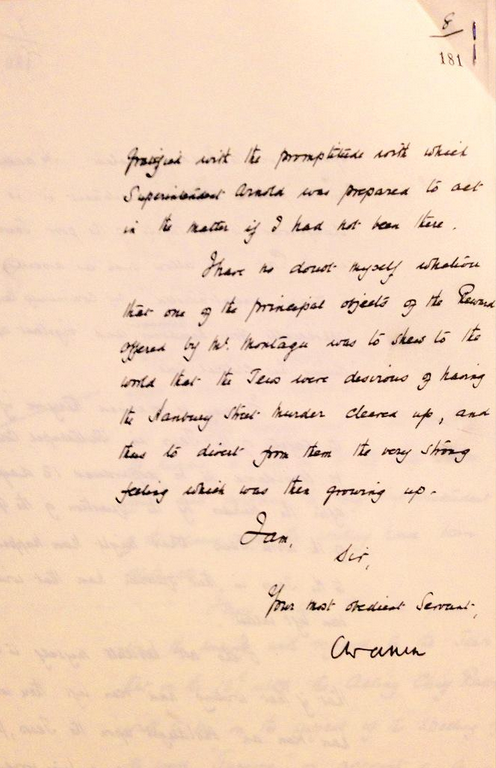

I have no doubt myself whatever that one of the principal objects of the Reward offered by Mr. Montagu was to shew to the world that the Jews were desirous of having the Hanbury Street Murder cleared up, and thus to divert from them the very strong feeling which was then growing up.

I am, Sir,

Your most obedient Servant,

(signed) C. Warren

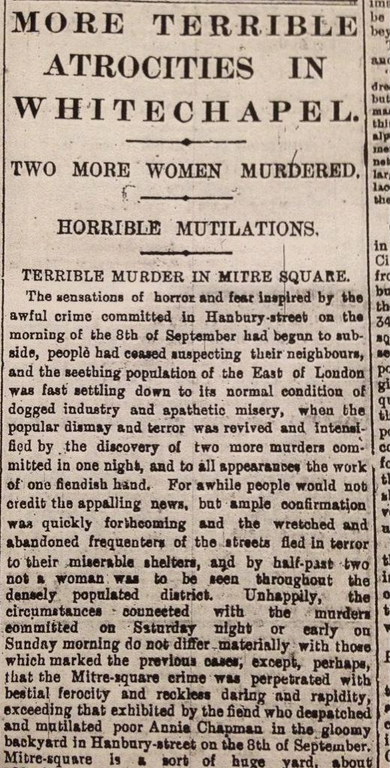

Atchison Daily Globe

Kansas, USA

17 October 1888

LONDON’S DISGRACE

SIR CHARLES WARREN AND HIS PACK OF HOUNDS

After He Tried Them by Letting Them Loose on His Own Trail He Turned Them Out to Follow Other Trails, and They Got Away – A Horrible Letter.

London had begun to forget all about the horrible Whitechapel murders, when one morning not long ago the great metropolis was shaken from the innermost recesses of the city to the elegant suburbs that have been lately built for the occupation of the wealthy and cultivated by the announcement that Sir Charles Warren’s dogs were loose. Sir Charles had for some time been training these dogs, with a view to having them track and tree (sic) the human fiend who has been operating in Whitechapel, whenever that shrewd ghoul should kill another victim. All the world remembers how much Sir Charles banked upon his bloodhounds and how he made himself a laughing stock of everybody by letting them chase his august person one every early morning not long ago. One would imagine that his experience would have shaken his faith in the wisdom of the scheme, for, so the account runs, they only succeeded in making even a fair showing one time in three.

The fact is, almost any one conversant with the employment of hounds for tracking persons will tell you, it is quite a different matter for a dog to take up and follow a scent across a sparsely settled country, and through the intricate mazes of a densely-populated city.

It is not at all uncommon for a dog to quite lose the scent in the former instance because of one crossing track. In a crowded metropolitan district like Whitechapel, where any given track would be criss-crossed by tens of thousands of other tracks inside of an hour, the task of following the murderer by the scent would be altogether beyond the power of even the keenest nosed dog.

And even if Sir Charles’ experiments had been successful to a marked degree; the results would have justified no sanguine expectations. For the experiments were made early in the morning when few people would be stirring, and the chance of obliteration by subsequent trails would be at the minimum, whereas the search for the murderer would, very likely, have to be made at a busy time of the day.

When Sir Charles lost the dogs, he was trying them in the open country. They had been taken to a common in the suburbs and there “laid on scent after scent.”

Whether they showed any progress in the noble art of man hunting is not stated, but when let loose on what proved to be their last run they were “lost sight of altogether”, and “the men in charge were frantic.” Certain capers at Sir Charles’ method of running the police department have suggested that “perhaps some smart dog fancier has made a great haul of the prize hounds.”

It is quite possible that this last exploit of Sir Charles Warren will move the London publications that sail under comic colours to the printing of cartoons bearing upon the subject. Punch has already devoted considerable attention to the Whitechapel matter, and here is a reduced reproduction of one of its cartoons, heading and all:

THE NEMESIS OF NEGLECT IS SHOWN HERE

Sir Charles Warren is a most extraordinary person, if we may believe the English newspaper stories about him. He doesn’t seem to have the slightest qualification for the position of chief of police, and the office came to him only because he was born with patrician blood in his veins.

He has been a soldier, and a fairly good one, too – serving abroad – and therein, perhaps, lies much of the secret of his ill success. If he had been willing to act simply as a figure head, let other and more capable men attend to the executive part – the real work of the department – matters would probably never have reached such a pass as to render the Whitechapel murders possible.

But, having won some reputation as a fighter of savages, he felt that he knew just how to preserve order in a city largely composed of civilized people. Brooking no interference with his plan of conducting the affairs of the office of chief of police on the lines of a military campaign, and fully imbued with the idea that the chief end of the police is to suppress free speech and all sympathy with the Irish, whom he hates so bitterly, he devoted his energies to closing public places to speakers who are dissatisfied with the existing order of things in England and the following and arrest of Americans and others supposed to have a friendly feeling towards Erin’s green isle. Of course, it was not long before the Scotland Yard men and the “bobbies” alike expended whatever abilities they possess in these directions, and what are on other countries are considered the most hateful classes flourished unhurt and plied their criminal callings unmolested. In this connection are presented portraits of Inspector Hailstone and Coroner Baker, two officials who have ably seconded Sir Charles Warren’s policy of marked incapability.