The Whitechapel Murders

It is often said that Jack the Ripper had five victims, collectively known as the ‘canonical five’; they are Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Kelly, all murdered in a ten week period in that fateful year of 1888. However, the Whitechapel murders, as they were considered at the time, before the case began to be dissected by ex-police officers and theorists, were a much larger series of crimes, beginning in April 1888 with Emma Smith and ending in February 1891 with Frances Coles. As time has gone by, some of the women murdered have been reconsidered as being Jack’s work also. The jury, as always in this case, is still out.

The idea of a single perpetrator did not emerge immediately and even today, it is suggested that somebody needs to murder three or more people over a period of one month to be deemed a ‘serial killer’. The FBI, putting forward their own criteria, even go so far as to say that the definition of serial killing is “a series of two or more murders, committed as separate events, usually, but not always, by one offender acting alone.” There also needs to be evidence of a ‘cooling off period’ between murders to differentiate the crimes from a spree killing or an act of mass murder.

Before the death of Mary Ann Nichols on 31 August 1888, there were two murders which caused great outrage in the East End, remarkable considering that this part of London had no doubt become used to stories of vice and crime. By the 1880s, the neighbourhoods of Whitechapel and Spitalfields, as well as nearby districts like Bethnal Green and Poplar, exhibited some of the most scandalously poor living conditions in London. The East End had, in parts, become an overcrowded slum, which over the years had struggled to cope with the sheer number of people choosing to live there. Much of this was down to the fact that it was home to many of the so-called ‘stink industries’, such as breweries, slaughterhouses and refineries, which had attracted many migrant workers to the area during the industrial revolution. Its proximity to the mighty Thames and the docks ensured that immigrants arriving in London would find their first point of entry in places like Wapping, Limehouse and of course, Whitechapel. In effect, the East End had become a great melting pot of different classes and cultures, generating its own frictions and ultimately, problems.

The issue of housing the masses of this densely populated area was one of those problems. Whereas parts of Whitechapel and Spitalfields had once been prosperous and semi-rural, demand dictated that gardens were built over to provide accommodation, often only accessible from narrow alleyways and courts. These squalid dead-ends became the homes of the desperately poor and the criminal element who could use the anonymity of an enclosed passageway to hide from the law. Homes that had once been grand properties owned by successful Huguenot silk-weavers in the 18th and early 19th century had now been vacated by their well-off tenants and were sublet, often with entire families occupying a single room without the benefit of effective sanitary facilities. A major scourge in the area were the Common Lodging Houses, or ‘doss-houses’ as they became known, properties owned by private landlords that catered for the transient and the homeless, where a bed could be bought for as little as four pence per night. Spitalfields in particular had a great concentration of such houses and with owners obviously happy to take money from any available source, often allowed petty criminals and prostitutes to stay, sometimes turning a blind eye to what was going on under their roof. The neighbourhood around Commercial Street was particularly notorious and names like Dorset Street, Thrawl Street and Flower and Dean Street would become synonymous with dire poverty, crime and ultimately, the victims of Jack the Ripper.

It was around this area that the series of crimes known as the Whitechapel murders began in early 1888. The first two women killed lived in the dark heart of the Spitalfields doss-house district and died close by in mysterious and appalling circumstances. Whether they were the work of Jack the Ripper is still debated today, but what is certain is that they are an important prelude to what happened later. They stirred an underlying concern for the welfare of those who lived below the poverty line in the East End and tentatively raised questions about what should be done to alleviate the problems that had been swept under the carpet for so long; and by their very violent nature, they kick-started an anxiety that would soon grow into a mass panic.

The Murders Begin

Between 4.00 and 5.00 a.m. on the morning of 3 April 1888, Emma Smith entered her lodging house at 18 George Street in a terrible state. Her face was bloodied, one of her ears had been torn and she was suffering excruciating pain from an injury to her abdomen. She told Mary Russell, the deputy of the lodging house, that she had been set upon by a gang of three men who had assaulted her and robbed her of what little money she had. Even though she did not describe her attackers, she did comment that one of them looked to be about nineteen years of age. Mrs. Russell, assisted by another lodger, convinced Emma to go to the London Hospital on Whitechapel Road. As they made their way there, passing down Brick Lane to Osborn Street, Emma pointed out the spot where the outrage occurred, by a cocoa and mustard factory near the corner of Wentworth Street and Brick Lane.

At the hospital, Emma was attended by Dr. George Haslip, who was told the story of what happened. She had been walking by St Mary’s Church on the Whitechapel Road at about 1.30 a.m. and seeing a small group of men ahead, had crossed the road to avoid them, probably because they appeared unruly or threatening. Unfortunately, they followed her up Osborn Street and attacked her outside the cocoa and mustard factory. Dr Haslip’s subsequent examination revealed the extent of Emma’s injury to the lower abdomen; a hard instrument, probably a stick, had been thrust into her vagina with such force that it had ruptured the perineum. Emma began to grow increasingly weak, eventually falling into unconsciousness, and there was little the hospital could do – at 9.00 a.m. the following morning, 4 April, she passed away, the cause of death being peritonitis, a direct result of that brutal injury.

Three days later, a coroner’s inquest was convened, the purpose of such proceedings being to ascertain the cause of death (rather than the identity of the perpetrator). It was here that the last hours of Emma Smith were ascertained. On the evening prior to the attack, the Easter bank holiday Monday, she had left the George Street lodging house at about 6.00 p.m. At some point she had made her way to Poplar where she was seen by fellow lodger Margaret Hayes, who was leaving the area after being punched by a man in the street a short while before. It was 12.15 a.m. and Emma was apparently talking to a man of medium height, who was wearing a dark suit and white silk handkerchief round his neck. The next time she was seen was when she arrived at the lodging house in distress. The inquest lasted a day and a verdict was reached of “wilful murder against some person unknown.”

The official reports into what was obviously now a murder case have since gone missing, but notes were taken from some of them prior to their disappearance, one being a report by Inspector Edmund Reid of the Metropolitan Police’s H, or Whitechapel, division. In it, Reid had noted down some biographical details about Emma Smith; apparently she had a son and daughter living in the Finsbury Park area of north London and had been living at 18 George Street for about eighteen months. She was in the habit of going out at around 6.00 p.m. every night and often returned home very drunk. Further information gleaned from the press stated that when drunk she could sometimes behave like a ‘madwoman’ and on one occasion came home to the lodging house claiming to have been thrown out of a window. Although these accounts reveal a rather boisterous character, it is about as much as is known about Emma Smith, apart from the suggestion that she was a widow and the very likely probability that she was a prostitute.

Naturally, the death of Emma Smith received some coverage in the press, where it was described as the “horrible affair in Whitechapel” and that Emma had been “barbarously murdered.” In his summing up at the inquest, even coroner Wynne Baxter was moved to comment that “It was impossible to imagine a more brutal and dastardly assault.” However, Emma’s attackers were never caught. Her story is a mysterious one, for there are a number of questions which remain unanswered; why did it take so long (about three hours) to travel the 300 yards from the scene of her attack to her lodging house? And why did none of the policemen on the beat in the area see or hear anything about the attack at that time? And why did Emma appear reluctant or unable to describe the men other than mentioning that one was quite young? Was she telling the truth?

These are just some of the questions that have been raised over the years and perhaps the answers would be forthcoming if the original investigation reports were still available. The fact that all evidence points to an assault by a small gang intent on robbery suggests that Emma Smith was just the victim of organised crime, an outrage that was intended to humiliate rather than cause death. It is possible that the Ripper was indeed part of that gang, choosing later to work alone, but it is merely supposition unsupported by hard evidence. The suggestions by some researchers that Emma Smith may have been attacked by the Ripper working alone and that she used the gang story to deflect attention from the reality that she was soliciting that night are suppositions at best and I feel it is always necessary to go with the written record. Besides, in her circumstances, suffering the effects of considerable trauma and pain, I see no reason to assume she would, or even could, go out of her way to fabricate a cover-story.

***

Bank holidays were no doubt a time when prostitutes would be able to benefit from the large number of potential clients who, enjoying an uncustomary day off from the daily toil, would take advantage of the various entertainments on offer, including the pub. Men, loosened up by alcohol and a sense of freedom, would very likely have the pick of the local ‘fallen women’ as they worked around the licensed houses, music halls and riverside areas of the East End. However, with such opportunism also came risk. With drink perhaps influencing behaviour or local criminals wise to the abundance of prostitutes in the area, the women surely had to have their wits about them to avoid being robbed or ill-used by their clients. It is therefore unsurprising that the next Whitechapel murder took place, like the first, after a bank holiday Monday. The victim was Martha Tabram, found murdered in the early hours of Tuesday, 7 August 1888.

Martha Tabram was 39 years old at the time of her death – born Martha White in Southwark in 1849, she had married Henry Tabram in 1869 and they had two sons. Unfortunately, the couple separated in 1875 owing to Martha’s continuous heavy drinking and from thereon she had fallen into a destitute life. Henry initially supported his wife financially, until he discovered that she was co-habiting with a carpenter named Henry Turner, at which point he stopped giving her money. To earn their living, Turner and Martha hawked trinkets at the markets and on the streets and by 1888 were living in a room in a house off Commercial Road. But Martha’s drinking affected this relationship too – she was given to fits when very drunk – and sometimes they would separate, during which time Turner had no idea how Martha conducted herself. In July 1888, they parted for the last time. From here on in, Martha probably earned money through hawking and casual prostitution.

After Turner left her, Martha took up lodgings in Spitalfields, at 19 George Street, the doss-house next door to where Emma Smith had been living previously. At the time of her murder she was described as plump, 5 ft. 3 in. tall with a dark complexion and dark hair. At approximately 4.50 a.m. on the 7 August 1888, she was found by John Reeves, a labourer, lying on her back in a pool of her own blood on the first-floor landing of a tenement block where he lived in George Yard, Whitechapel, known as George Yard Buildings.

Upon discovering the body Reeves ran to find the nearest policeman, who turned out to be PC Thomas Barrett, on duty in Wentworth Street close by. After seeing the body, PC Barrett immediately sent Reeves to fetch Dr. Timothy Killeen from his surgery at 68 Brick Lane, who on arrival at 5.30 a.m. pronounced Martha dead at the scene. The body was soon taken to the mortuary in Old Montague Street, where a photograph was taken and a post-mortem conducted. In his report, Dr Killeen observed that Martha had received 39 separate stab wounds to various areas of her body. The lungs were pierced multiple times, as well as her heart, liver, spleen and stomach. He also believed that two different weapons had been used; one was a small pen knife, no bigger than a few inches, which had caused 38 of the wounds, the other weapon being a large knife thought to be similar to a bayonet, around 6 inches or more, the cause of a single injury which had penetrated the breastbone.

George Yard Buildings had many residents and it is therefore remarkable that nobody in the tenement heard any cries or commotion during the night. Significantly, just over an hour before Martha’s body was found, a young cab driver named Alfred Crow had ascended the staircase and saw somebody lying on the first-floor landing, but as we was accustomed to seeing people sleeping rough there, took little notice. The lights inside George Yard Buildings were turned off at 11.00 p.m., so it was probably not light enough for him to see that Martha Tabram was dead.

With an obvious murder having been committed, potential witnesses were sought, but the only one who was able to shed any light on the last hours of Martha’s life was another prostitute by the name of Mary Ann Connelly, commonly known as, ‘Pearly Poll’. After hearing of the murder, she went to Commercial Street Police Station and claimed that she and Martha had spent much of the previous night visiting the pubs of Whitechapel. They had met two soldiers at about 10.00 p.m., one a corporal and the other a private. They continued to drink together and at approximately 11.45pm they separated on Whitechapel High Street. Martha went with the private into George Yard and Connelly accompanied the corporal into Angel Alley, a few yards away. This was the last confirmed sighting of Martha before she was found murdered. Connelly declared to the police that she would be able to identify the two soldiers.

Detective Chief Inspector Edmund Reid headed the murder investigation and arranged an identity parade at the Tower of London, on the strength of Connelly’s claims. All the soldiers from the grenadier guards regiment who were on leave that evening were brought for inspection. The parade was attended by PC Barrett, who said that at about 2.00 a.m. on the morning of the murder he had seen a private of the Grenadier Guards standing at the corner of George Yard and Wentworth Street; when questioned, the soldier said that he was waiting around for his “chum”. At the parade, Barrett picked out a private before changing his mind and selecting a second man, who appeared to have strong alibis as to his whereabouts on that fateful night. Mary Ann Connelly, however, failed to turn up.

She was eventually found by Sergeant Eli Caunter staying with a cousin near Drury Lane and so a new parade was arranged for 13 August , which she did finally attend. She failed to pick out the two men that she and Martha were with that fateful evening. Whilst there, she mentioned that the men they were with had white bands around their caps, meaning they were from the Coldstream guards. This rearranged identity parade appeared to have been a waste of time as the wrong group of soldiers had been targeted for identification.

Two days later, Connelly was taken to Wellington Barracks where she picked out two soldiers, known as George and Skipper, whom she said were without doubt the two men that she and Martha had been with. Both the soldiers were interviewed and after extensive investigation, their whereabouts were confirmed and they were found to be nowhere near the Whitechapel area on the night of the murder. Other soldiers were investigated, having their bayonets checked and their whereabouts on the night of 6 – 7 August ascertained. After all reasonable enquiries into the murder of Martha Tabram were exhausted, the investigation appeared to fizzle out.

At the inquest, the jury yet again delivered a verdict of “wilful murder, by person or persons unknown.”

The murder of Martha Tabram typified the difficulties that the police at the time faced. Evidence was often built on vague eye-witness statements that could not be confidently corroborated and as a result the police had no further reliable information to pursue a valid route of enquiry.

The murder of Emma Smith, four months previously, had obviously stuck in the minds of the local people and the press. It was commented on that these two murders were committed within very close proximity to each other and that both victims were of the same class and lived in the same disreputable neighbourhood. The timing, both being on a bank holiday night, was also noted. It is impossible to know if these two murders were truly linked, committed by the same person (or persons), but it has often been said that unlike Emma Smith, whose death appears to be gang-related, Martha Tabram may have been killed by Jack the Ripper. It is an idea that I can understand and it would be impossible for me to discount her as the Ripper’s first ‘tryout.’

Nonetheless, these events should have increased the police awareness of a sudden rise in violence against prostitutes in the area. If they had been more astute to the situation, the police may have been able to put into place measures that could have prevented further killings, namely those now commonly attributed to Jack the Ripper. However, they unfortunately did not learn from these two shocking events and as a result, five more East End ‘unfortunates’ met a progressively bloody end.

I sit in Mitre Sq and ponder on the fact that the Ripper and the 4th murder victim walked here via that passage…

The street prostitutes would stand here to offer their services to the sailors who came up from the nearby docks…

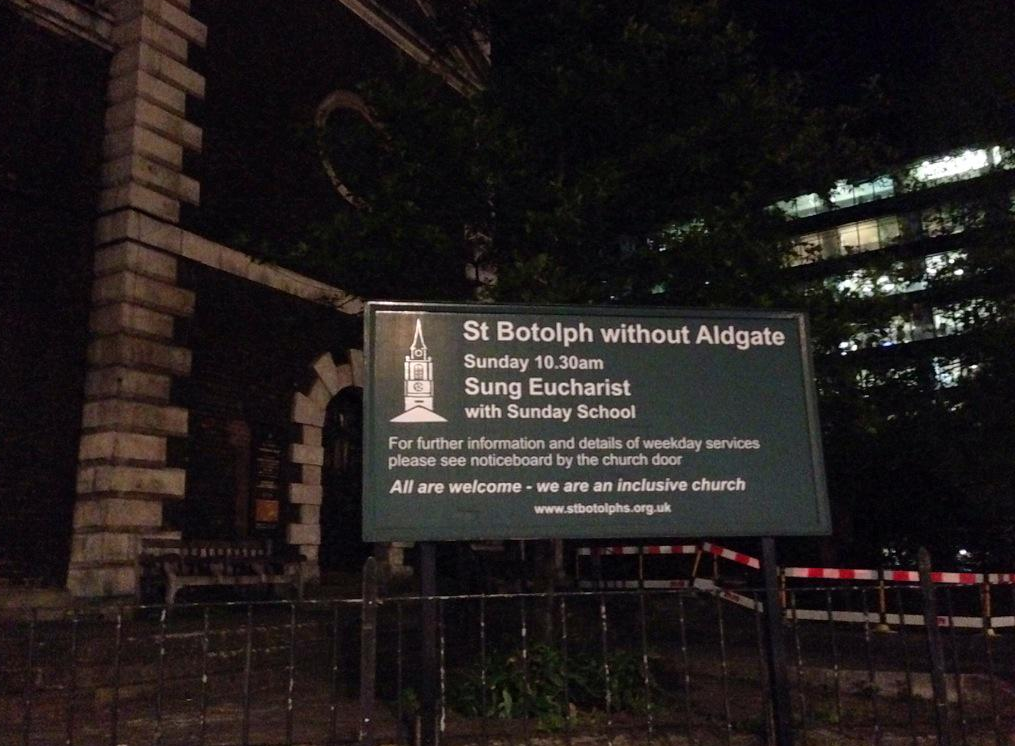

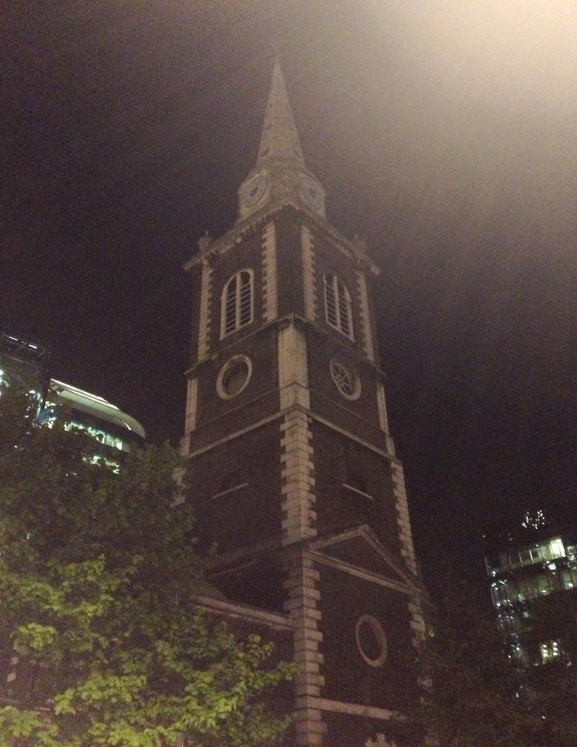

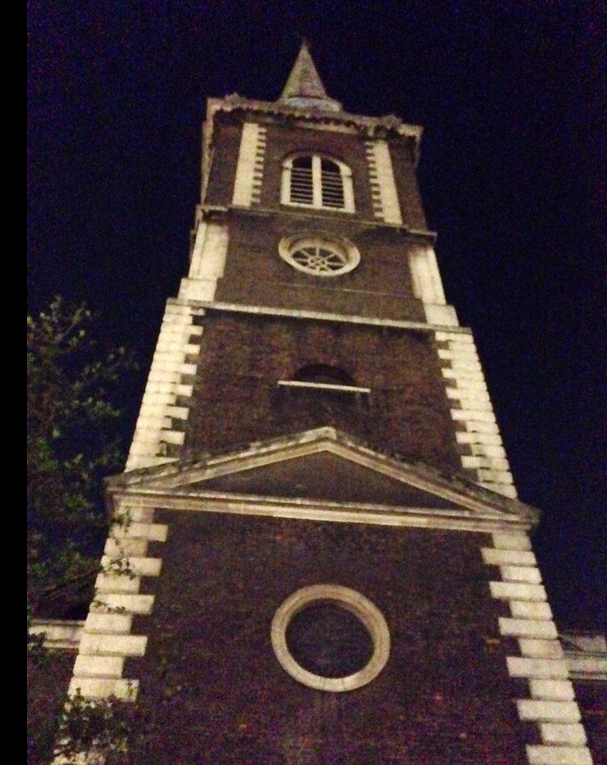

Walking to Brick Lane past St Boltolphs church, I realise that the Ripper found his victim very near here…