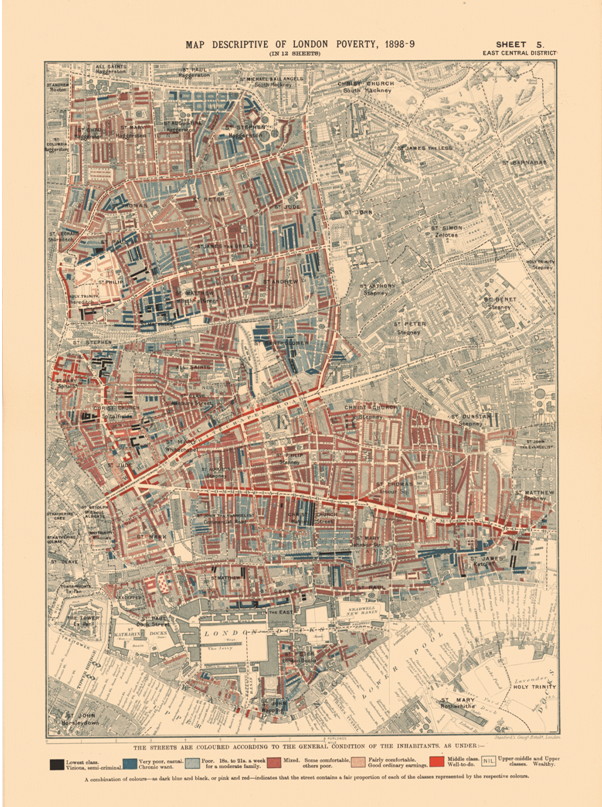

For centuries the East End had been a great melting pot, and until this massive flood of immigrants it had dealt well with incomers, but now it was stretched to breaking point, and anyone who could afford to move away did, leaving a population who were, by and large, scraping by.

Survival was the key, food and lodging the most important aims. Typhoid, cholera and venereal disease were rife, and the area had the highest birth rate, the highest death rate and the lowest marriage rate in the whole of London.

Housing was the big problem. Whereas parts of Whitechapel and Spitalfields had once been prosperous and semi-rural, demand throughout the early to mid-1800s resulted in gardens being built over to provide accommodation, often only accessible from narrow alleyways and courts.

These squalid dead ends were the preserve of the desperately poor and the criminal element, who could use the anonymity of an enclosed passageway to hide from the law. Sanitary facilities were appalling: for example, in one Spitalfields tenement near Brick Lane, sixteen families shared a single outside lavatory which did not seem to be cleaned regularly and which, shockingly, was next to the only source of running water for the inhabitants, a single water tap.

Children were born and brought up here, although 20 per cent of them failed to reach their first birthday. They worked to earn money as soon as they could, sweeping pavements, cleaning windows and scavenging food from the rubbish in the streets, until they were big enough to work in the ‘sweaters’ (sweat shops) doing tailoring and other work for long hours and very low pay. Some of them formed small bands of skillful pickpockets.